The TPP – Good for U.S., Australian and New Zealand Exports and Malaysia & Vietnam’s Processing Trade

Details of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal have now been released, with both the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade placing the complete text in the public domain for the first time.

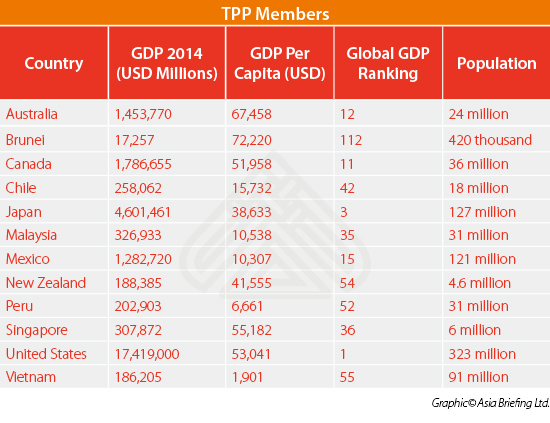

The deal, which still has to be approved by the U.S. Congress, effectively eliminates tariffs on specific goods traded between TPP member nations. These are: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States and Vietnam.

Here are my initial comments on the agreement now that the text has been released.

It’s Not a U.S. Trade Deal

Early, knee-jerk commentators have tended to concentrate on the U.S. aspect of the TPP and portray it as a U.S. agreement. In fact, the United States came to this particular trade party relatively late. The original agreement (then called the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership) was signed off in 2005 between Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. The U.S. didn’t begin negotiations to join until 2008. Also, the TPP is a multilateral agreement between all members, not a bilateral agreement between the U.S. and ‘everybody else’. Comments such as “The U.S. writes the rules, not China” are misguided, inappropriate and fail to acknowledge the other participating nations.

The U.S. involvement in the TPP is important because of the size and value of the American economy, and the impact of U.S. politics on anything involving their domestic markets. But the TPP is not purely an American deal, and suggestions that it is are misplaced. It impacts on trade between Australia and Vietnam, Japan and Mexico or any combination of members just as much as it does the United States. This means that tax and trade advisory from each individual member nation is required to examine content and to ascertain how the TPP impacts on their trade position with all TPP members, and not be restricted purely to comment from the perspective of the United States.

The TPP Includes 18,000 Products and Eliminates Tariffs

This may sound a lot, but the TPP deal is not a blanket elimination of tariffs. The 18,000 products mentioned include many related parts pertinent to very specific industries, such as automotive. While 18,000 sounds huge, it isn’t when considering that just one typical American and Japanese (both TPP members) vehicle contains over 30,000 component parts. This means the TPP needs to be studied carefully for the industries it actually does impact upon.

Understanding the TPP Member Nations

Getting a handle on the TPP is an important part of appreciating what it is intended to do. There seems little in common to unite Canada and Peru for example. But let’s start by taking a quick look at each of the TPP economies:

TPP Member Disparity

We can briefly illustrate the disparity between TPP economies as follows:

GDP

Highest: United States (USD17.42 trillion)

Lowest: Brunei (17.26 billion)

Population

Highest: United States (323 million)

Lowest: Brunei (420 thousand)

GDP Per Capita

Highest: Brunei (USD72,220)

Lowest: Vietnam (USD1,901)

This data reflects the disparity between TPP members, from giants to minnows. It is little recognized that the TPP contains two of the world’s top three economies (China is the odd man out) and a quarter of the top 20. Yet it also includes far smaller economies. Why is this?

Part of the rationale behind the TPP is to allow the wealthier member nations to upgrade manufacturing and production facilities in cheaper cost member countries. Feeding these smaller TPP member economies both the investment and the raw materials to import and process these goods allows the more advanced TPP nations to continue to import relatively low cost, yet high quality, added value products back to their own consumer markets. This means that countries such as Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru and Vietnam, with their lower cost bases, will see investment from the wealthier TPP countries to allow them to manufacture and process products at good value levels.

Labor costs in TPP member nations such as Australia, Canada, Japan, Singapore and the United States are relatively high. Yet the TPP allows manufacturers in these countries a cheaper labor alternative to process, and add value to their products elsewhere with the TPP membership. Raw materials and higher technologies will continue to be produced in the wealthier countries, but processing will be completed at lower costs elsewhere. That keeps for example American, Australian and Japanese manufacturers of high quality raw materials and their industries in business and ultimately benefits the eventual end consumer, as total production costs can now be mixed between high and low wage cost options.

This ‘swap’ deal is in effect using lower manufacturing costs in these smaller TPP countries while also allowing them access to these wealthier markets at the same time. The TPP agreement in one sense exchanges cheap manufacturing facilities for export potential.

Brunei is in the mix for its oil and gas industry, and can provide a market for exports of processing and refining equipment, in addition to encouraging regional processing for TPP members Australia and Malaysia, both of whom have significant crude of their own.

This of course has implications for China. The country faces issues qualifying for TPP membership anyway, due to non-compliance in certain commerce sectors in which the government retains control (such as the internet, banking and government procurement), and is also paying the price for decades of lip service towards intellectual property protection. China is also at a disadvantage for raising the mandatory labor costs in the country in too fast a manner. There was little thought for phasing this in over a longer period of time, as the CCP wished to maintain domestic political popularity by increasing the wealth of Chinese nationals. It is unknown whether this is a sustainable trend in China’s economy or may be shown to be a strategic mistake. It also remains arguable that this issue is in fact responsible for the China slowdown that is now occurring. The problem for the China manufacturing industry is that it may have priced itself out of the market and has now become uncompetitive. The TPP presents an alternative to China production in certain industry sectors.

TPP Tariff Reductions Impacting Positively Upon U.S. Exporters

The TPP reduces tariffs on imported goods for numerous items that will impact positively on American manufacturers in a number of industries. In effect, this counter-balances advantages that China has under its own FTA with ASEAN and similar agreements that the United States is not signatory to. Not being part of these has meant that Canada, Mexico and the United States in particular have endured a trade disadvantage when compared to China. It should be noted that collectively, each of these countries are trillion dollar economies and represent some serious trade muscle that seems to have been strategically bypassed by China’s own FTA, trade agreements and bilateral trade policies. Beijing in this instance appears to have miscalculated the importance of the NAFTA region.

This omission has meant that, as an example, Vietnamese auto parts buyers pay a 27 percent tariff if they choose American or NAFTA manufactured parts, but only five percent or no tariff at all on similar Chinese- or Thai-made auto parts under the China-ASEAN FTA. This is obviously to the disadvantage of American and NAFTA auto component manufacturers. In the longer term, it will also be damaging to local manufacturing in ASEAN, as it denies them access to superior quality North American products and hinders them from eventually upgrading the quality of Asian made vehicles. China, after all, has often failed in its QC. The TPP offers alternative and often higher quality sourcing options in this regard.

As the USTR more specifically notes, prior to the TPP agreement actually taking effect, several TPP countries are imposing tariffs that translate into very high costs for buyers of North American products. For example, Malaysia charges tariffs of 30 percent on American autos, while Brunei has tariffs as high as 20 percent on machinery. Japanese tariffs on leather footwear can rise as high as 189 percent out of quota and 17 percent on fruits and vegetables, and even higher for oranges in season; Vietnam imposes tariffs averaging 9.4 percent on manufactured goods, with these tariffs often rising as high as 27 percent for auto parts and 68 percent for trucks. Vietnam also imposes high rates in agriculture, as high as 30 percent on cuts of pork. The TPP agreement will eliminate these, meaning new export trade benefits arise for the North American auto component, agriculture, textiles, oil & gas and machinery manufacturing industries. When coupled with a tougher IP stance also introduced under the TPP remit, there are more secure opportunities for the subsidiary industries that go hand in hand with these primary sectors – the fashion and consumer brands associated with them all being a case in point.

Another trend that may develop from this is more American-Australian ventures being established, especially in the Asian TPP hub of Singapore. Being able to call on Australian management, expertise and infrastructure with similar corporate mindsets, yet with the proximity of Asia close to hand, may well be a way for North American investors to both spread risk yet jointly develop mutually viable products for their respective markets.

TPP Benefits for Australian & New Zealand Exporters

Australia and New Zealand are not quite so impacted by the TPP as the United States, as they have already enacted an FTA with the ASEAN bloc known as the AANZFTA. That deal, which is being phased in, has eliminated tariffs on 67 percent of all traded products between ASEAN, Australia and New Zealand, and will expand to 96 percent of all products by 2020. The AANZFTA was the first time ASEAN has embarked on FTA negotiations which covers all sectors, including goods, services, investment and intellectual property rights, making it the most comprehensive trade agreement that ASEAN has ever negotiated. Details of this agreement may be found here.

In addition, Australia signed off an FTA with China last year that covered industrial sectors such as agriculture, mining, manufacturing and commercial services. When enacted, 85.4 percent of China and Australia goods will gradually be subject to zero tariff rates. Further, both countries will grant each other the most favorable nation (MFN) treatment, meaning that imports will be subject to MFN rates that are much lower than the general rates which apply to non-MFN nations. China is Australia’s largest trade partner, with 20 percent of Australian imports coming from China, and 36 percent of exports going to China, so the China deal has been important.

There is also an Australian FTA with Japan, and both Australia and New Zealand have signed FTAs with Malaysia. New Zealand meanwhile has its own FTA with China, as well as Close Economic Partnership Agreements – a watered down version of a full FTA – with Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and Thailand. Given that both countries are pretty well covered when it comes to Asia, what can the TPP offer Australian and New Zealand exporters?

Primarily, the main new trade area is with the United States, and possibly, should the ‘onshoring’ movement become more popular – possible in the event of oil prices surging – Mexico as well, which could be a manufacturing and processing conduit to access the U.S. and Canadian markets. Australian and New Zealand exporters are likely to find aquaculture (seafood) and their dairy and dairy farming products, such as beef and lamb, in demand. This is likely to be in tandem with further levy reductions for sugar into Japan; the elimination of the tariff on refined sugar into Canada; elimination of tariffs on raw sugar into Peru; and the wholesale licensing arrangements for supply of refined sugar to the food and beverage industries in Malaysia. This will be good news for companies manufacturing products for consumer sodas and soft drinks, as well as the brands themselves, and to some extent beer.

Overall, the Australian and New Zealand economies are quite open, so accepting high quality imported products from TPP members shouldn’t be so much of an issue. The main beneficiaries, apart from a significant boost to agriculture, would be oil, gas and mining equipment to Brunei and North America, and the potential, similar to the impact on American investors, to conduct processing and re-export businesses in Malaysia and Vietnam. It would not surprise me to see American-Australian JVs being set up in Singapore to then spread the financial risk, yet jointly develop a TPP processing strategy and investment in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, or any one of Malaysia’s economic processing zones. Such structures and partnerships may become increasingly common given the related benefits. There is no restriction in Singapore on the nationality of investors into any Singaporean corporate limited liability structure.

TPP Driven Investment into the Processing and Re-Export Industries

As mentioned, the TPP members have different costs and capabilities. I also previously discussed the impact of the TPP Yarn Forward provision and how it will impact upon Vietnam in particular. In essence, this provision is good news for exporters of textiles manufacturing equipment, as Vietnam and Malaysia in Asia, and Chile, Mexico and Peru in the Americas will need to source textiles from their own or other TPP markets and not from elsewhere in order to resell onto other TPP markets such as Australia, Canada, Japan and the United States. The issue here is that the production of textiles in these markets is not especially developed, and they will require assistance to build these industries. That means foreign direct investment coming in from the wealthier TPP nations. In fact, analysis has shown that TPP membership can be expected to add 15 percent to Vietnam’s GDP value, partly as a result of increased FDI.

The implications are clear. FDI will start to flow into Malaysia and Vietnam in Asia, as well as into Chile, Mexico and Peru in the Americas. Most of that will originate from Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States, as their quality textiles and agriculture, automotive, and other TPP impacted manufacturing industries have both the technology and the wealth to reinvest in these markets. Part of that Asian and South American production will be processing of raw goods to then be re-exported back to the home TPP member. Others will make their way onto the global market via agreements such as the AANZFTA and the ASEAN-China FTA.

Singapore as The Asian TPP Investment Hub

Singapore is also a member of the TPP, and while it doesn’t have a large manufacturing industry of its own it does have joint economic zones with both Indonesia and Malaysia. Singaporean companies are also large investors in the manufacturing industries across ASEAN, including next door TPP member Malaysia.

As a TPP member, the advantage that Singapore offers to investors from Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand and the United States is its services hub. It is a primary banking and financial center for reaching out to TPP members Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam, having for example both the only directly convertible currency in the region – the Singapore dollar is freely traded – and a plethora of Australian, Japanese and American banks. Coupled with this, it is a low tax jurisdiction (basic corporate income tax is 20 percent) and no dividends taxes are payable on profits repatriated from elsewhere. Singapore also possesses a highly valuable Free Trade Agreement with the United States in its own right, which contains many attractive provisions for American companies and their American employees to establish business and work in Singapore.

The city-state has beneficial Double Tax Agreements with other TPP members Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico and New Zealand. All of these can be further utilized to reduce the overall tax burden. Understanding these and taking professional advice about using them, and using a Singaporean company as an investment hub, allows beneficial tax advantages to investors from these markets. Utilizing a Singaporean company as a vehicle to additionally invest in Asian TPP members such as Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam when considering setting up a processing or other factory in these locations is a sound and proven investment strategy.

The TPP. What Happens Next?

The TPP agreement still has to be passed by the U.S. Congress and also debated and ratified by several other TPP member states. This will take time. It should also be noted that part of the TPP deal is to be phased in over a period of years. It will likely not be until mid-2016 before we can start to see the TPP come into effect.

Which are the Markets to Invest in?

In Asia, for the reasons discussed above, the TPP will attract FDI and investment into production and processing facilities away from China and towards Malaysia and Vietnam. Singapore meanwhile is a highly resourceful regional hub. Our sister websites, ASEAN Briefing (which includes Malaysia and Singapore) and Vietnam Briefing are the first ports of call for articles and intelligence about investment into these markets. Recent TPP articles produced by us in these markets include ongoing assessments of the TPP impact on ASEAN overall, as well as Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam. As I mentioned, the TPP is not purely an American agreement and requires a detailed understanding and experience of these local markets in Asia (and elsewhere) in order to fully appreciate the opportunities that the TPP can provide.

Reaching Out to TPP Asia – Malaysia, Singapore & Vietnam

To assist with this, our practice also has well established offices in the TPP member nations of Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, in addition to our extensive presence in China and India. Please see the contact details on any of these office links or email us at asia@dezshira.com for advice concerning the TPP agreement and opportunities for investors in these markets. We also retain legal and tax personnel in-house with American, Australian, Canadian, Japanese and New Zealand expertise and qualifications.

Reaching Out To TPP North America – Canada and the United States

To cater to the U.S.-Asia time difference and to enable us to service our North American clients immediately and efficiently, the practice maintains a fully staffed desk in Boston, MA. Companies in the United States and Canada may contact our office during normal East Coast Pacific times at USA@dezshira.com for advice concerning the TPP. The contact is Richard Cant. The practice also employs American legal and tax counsel.

Reaching Out to TPP Mexico and South America

For Chile, Mexico and Peru, we are members of the Leading Edge Alliance of international accounting and consulting firms. We have member firms operational in these markets. Please contact us at info@dezshira.com to reach out to these practices.

|

Chris can be followed on Twitter at @CDE_Asia. Stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends in Asia by subscribing to our complimentary update service featuring news, commentary and regulatory insight.

|

![]()

Doing Business in ASEAN

Doing Business in ASEAN

Doing Business in ASEAN introduces the fundamentals of investing in the 10-nation ASEAN bloc, concentrating on economics, trade, corporate establishment and taxation. We also include the latest development news in our “Important Updates” section for each country, with the intent to provide an executive assessment of the varying component parts of ASEAN, assessing each member state and providing the most up-to-date economic and demographic data on each. Additional research and commentary on ASEAN’s relationships with China, India and Australia is also provided.

Import & Export in Vietnam: Key Industries & Free Trade Agreements

Import & Export in Vietnam: Key Industries & Free Trade Agreements

In this issue of Vietnam Briefing magazine, we discuss the key aspects of Vietnam’s import and export landscape, focusing on textiles, telephones and computer products, and automotive parts. We then analyze opportunities for Vietnam among its inclusion in multilateral regional trade blocs, before examining the European Union-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement in detail. Finally, we give an overview of the requirements for establishing a trading company in Vietnam.

Investing in Vietnam: Corporate Entities, Governance and VAT

Investing in Vietnam: Corporate Entities, Governance and VAT

In this issue of Vietnam Briefing Magazine, we provide readers with an understanding of the impact of Vietnam’s new Laws on Enterprises and Investment. We begin by discussing the various forms of corporate entities which foreign investors may establish in Vietnam. We then explain the corporate governance framework under the new Law on Enterprises, before showing you how Vietnam’s VAT invoice system works in practice.

- Previous Article Getting Growth into Asia – the ASEAN Option

- Next Article How U.S. Companies Can Access the ASEAN, Chinese & Indian Domestic Markets Via the TPP Agreement