Prospects for UK FTA with China, Revitalization of Commonwealth

The UK has been in the business of negotiating free trade, or what were previously known as “Treaty Agreements” with China since 1842. The Commonwealth of Nations, meanwhile, has its roots way back in 1887, when the first of several British Imperial Conferences was held in London. These roots are of interest, as despite subsequent negative historical coverage, and much hand wringing among the politically correct, the British Empire ultimately led to the creation of modern India, Hong Kong, and mainland China. Without British influence at that time, these countries and territories would not be in the same format as they are now.

The first Treaty Agreement the UK had with China, the Treaty of Nanjing, covered the following clauses as concerns trade (others dealt with war reparations and other unfair impositions upon China, however for the purposes of this article, I concentrate purely on the trade aspect and leave the political material elsewhere). The Treaty of Nanjing’s trade clauses’ fundamental purpose was to change the framework of foreign trade imposed by the previous trade agreement, known as the Canton System, which had been in operation since 1760 – some 82 years – and had not been negotiated directly by the British government, but by appointed agents (The British East India Company). Those 82 years even then were a long time in underlying trade protocols between two large economies, even if one was the dominant world power.

The treaty abolished the former monopoly of the Cohong, and their Thirteen Factories, essentially joint ventures, in what is now Shamian Island in Guangzhou. The Cohong were a group of Chinese merchants, and the factories foreign-invested enterprises who were licensed to do business in China exclusively via the Cohong.

![]() Pre-Investment, Market Entry Strategy Advisory Services from Dezan Shira & Associates

Pre-Investment, Market Entry Strategy Advisory Services from Dezan Shira & Associates

Instead, in addition to Guangzhou, four additional “Treaty Ports” were opened up for foreign trade, namely Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. The need for Cohong merchants was also abolished, leaving foreign traders free to do business with whomever they wished. (The Guangzhou Cohong merchants must have been livid). The treaty also stipulated that trade in the treaty ports should be subject to fixed tariffs, which were to be agreed upon between the British and the Chinese governments.

Other clauses within the Treaty dealt with the subject of Hong Kong, which was added as something of an afterthought. Hong Kong island was included as a place to provide British traders with a harbor where they could “careen and refit their ships and keep stores for that purpose”. It was granted in perpetuity, with subsequent amendments to the treaty adding in leases to adjoining territories in Kowloon, and later the New Territories, including additional islands and parts of the Chinese mainland until the lease expiration of these additions in 1997.

In fact, once one takes out the colonial aspect and other unfair and one-sided articles of the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, China and the UK had in effect signed off on a free trade agreement, with tariffs set by both governments, and a free trade bonded zone, namely Hong Kong island.

The purpose I point out news that is so antiquated as far as prototype China-UK free trade agreements are concerned is that China and the UK have a lot of common ground and experience in working together on such matters. That is relevant in three areas today. Firstly, as the UK will, in the event of Brexit, need to renegotiate a free trade agreement directly with China; secondly, as EU negotiations with China have stalled, and terms have still not been agreed upon some 10 years after the commencement of talks. Mid-19th century Britain, in effect, was more effective at dealing with China than the EU is today, meaning the UK has a lot to look forward to in re-joining its past when it comes to modern China.

The third area deals with the role of multilateral institutions, and for that we must reexamine the nature of the (British) Commonwealth of Nations as well as look at modern China’s position on similar institutions of today. The Commonwealth of Nations (formally the British Commonwealth) traces its establishment back to 1926, although in reality a loose arrangement between member nations of the then British Empire had been connecting via London for the previous two centuries. Today, the body represents 20 percent of all global trade, and is headed up by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

The Commonwealth of Nations

Population: 2.2 billion

GDP: US$14.6 trillion

GDP Growth Rate: 7.1%

GDP Per Capita: US$6,222

Members: 53 nations

It may surprise many that the Commonwealth of Nations has been outstripping the EU in three determinants: population size, the size of the economy, and economic growth rate. These figures are from material recently published by World Tracker as well as the IMF, World Bank, and United Nations.

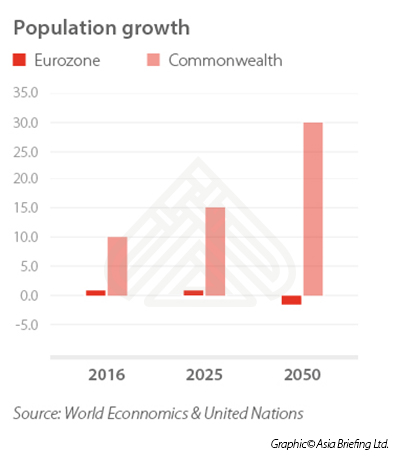

The graphic below shows the estimated population trends for the Eurozone compared with the Commonwealth for the 2016-2050 period. As can be seen, population growth in the Commonwealth alone is expected to rise by over 30 percent for this period, whereas the Eurozone population is expected to fall by 1.9 percent.

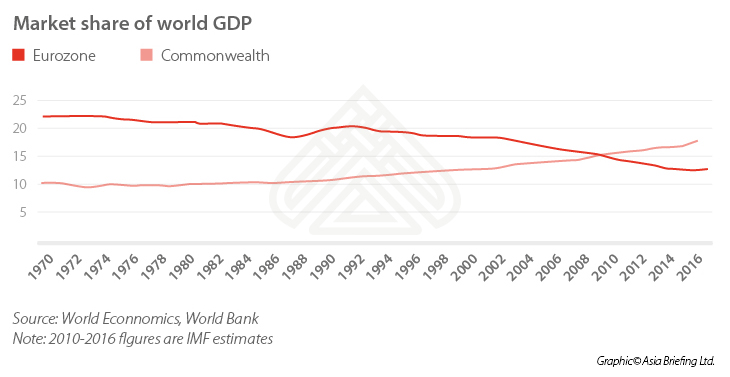

This graphic compares the Eurozone, EU, and Commonwealth from a market share of world GDP perspective, and shows the Eurozone and EU compared with the Commonwealth share of world real GDP.

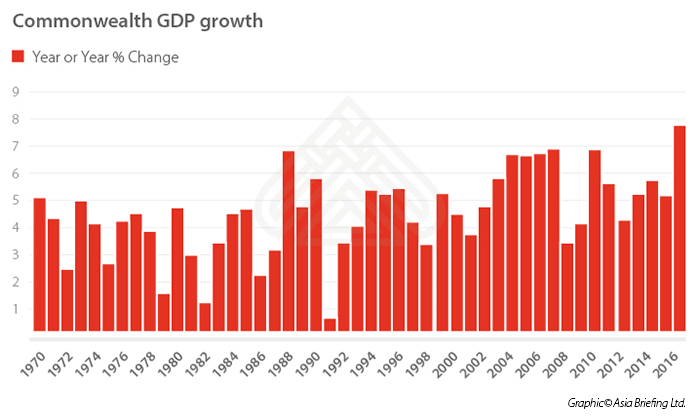

This final graphic shows the GDP growth in the Commonwealth has accelerated over the post 1973 period in sharp contrast to the EU, where the growth rate has been falling gently from an average of 3.6 percent in the 1970s to 1.7 percent in the past five years.

It may at this point be prescient to acknowledge that the British public, when faced with demographic votes concerning their future within the EU, may be smarter than Brussels had reckoned. The Commonwealth of Nations collectively is in rude health. What is missing, however, remains the British commitment to the Commonwealth of Nations as a driver for future UK growth and prosperity. This entails a great deal of negotiation and agreement between Commonwealth members, and especially as concerns the legalities and trade issues concerning collective rights among members, in addition to the imposition of common systems. Such a task would be a bonanza for Commonwealth IT and e-commerce experts, and could bring tremendous rewards for Commonwealth members as a whole.

However, the Commonwealth of Nations is considered deeply unfashionable and almost persona non grata by many British politicians and civil servants today. That is an attitude completely at odds with contemporary China and much of Asia, and is fast becoming outmoded in the modern era reshaping global diplomacy and politics. China, for example, has made giant strides in the last decade or so with its Shanghai Co-Operation Organization a political and dialogue entity that counts India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, and Uzbekistan as full members with China, and includes as observer nations Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia. Bangladesh, Egypt, and Syria have also applied for this status. Dialogue partners include Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkey, with applicants including Iraq, Israel, Maldives, Ukraine, and Vietnam. ASEAN, the Commonwealth of Independent States, Turkmenistan, and the United Nations are all Guest Attendees.

Russia, too, has its Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia and sits effectively between China and Europe. The EAEU has the capability to bring Chinese goods right to the borders of the EU, and its trade has been increasing. In many ways, the EAEU effectively acts as China’s OBOR Free Trade Area, and especially so when its own negotiations with it come to fruition

ASEAN is the Southeast Asian bloc comprising Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, and celebrates its 50th birthday this year. It conducts annual trade of some US$230 trillion. Five of the ASEAN nations have very strong historical connections with the UK.

There are several other examples, such as the Economic Union of West African States, the Arab League, and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), all of which contain countries with long standing ties to Britain.

China meanwhile has been re-inventing the wheel somewhat and has been active in promoting loose regional co-operative blocs, less formal in manner but nonetheless useful. Some include EU members, such as China’s grouping of the 16+1, an informal European-China bloc that includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. This grouping even has its own €10 billion investment fund, known as the China, Central & Eastern Europe Investment Co-Operation Fund, based in Luxembourg.

China has been motivating and incentivizing these nations to become prepared for new technologies and to act as a gateway for Chinese goods to enter Europe as well as for European goods to be prepared for the Chinese market. It is of interest to note, for example, that while Chinese-owned Volvo has announced it will only produce electric and hybrid cars from 2018 (a claim subsequently just taken up by Indian-owned Jaguar Land Rover), electric vehicle manufacturers in Romania and Bulgaria have recently been invested in by the new breed of Chinese auto investors. Volvo, meanwhile, remains a European brand – as does Jaguar and Land Rover with Britain. China is investing in and generating new technologies from Europe.

Going the other way in terms of future trade, it should also be remembered that China has a market of close to one billion online consumers and a middle class of some 500 million. They want to buy. The country is also energy poor and agriculturally poor – China possesses 20 percent of the global population but occupies just five percent of globally available arable land. This is why it has been developing its own trade institutions and initiatives to develop these, such as the One Belt, One Road project.

![]() RELATED: China – UK Trade: The Effects of Brexit

RELATED: China – UK Trade: The Effects of Brexit

The UK is on the right side of history, as long as it combines several development strategies together. They may not be historically happy or even currently politically correct; however, Empire was from a different nation to contemporary Britain. Hong Kong, signed off to the UK in 1842, has been a Chinese possession now for 20 years. That long-term China trade experience, deeper and more involved than that of most other nations, can be called upon in the spirit of free trade – after all, the Chinese aren’t getting anything out of the EU or the US right now. This, coupled with a British commitment to revitalize the Commonwealth of Nations, and bring those 53 member countries closer to China is a task that Britain alone is uniquely poised to provide.

The recent establishment and growth development of trade and dialogue blocs across Asia from ASEAN through to the EAEU, and the multilateral free trade agreements they have and are about to enter into is a way ahead. Britain has the Commonwealth of Nations, and a long history with China. It is unthinkable that today’s Beijing mandarins would stand idly by and let an asset such as the Commonwealth be forgotten and pushed out of sight. They would not, and their engagement in developing institutions and free trade illustrates the way ahead. In Britain, constructive debate on revitalizing the Commonwealth, mobilizing its members, and getting involved with Eurasia should be the starting point for a new British manifesto with engaging with China, and the new emerging partners that come with OBOR.

|

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner and Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates, and Publisher of the Asia Briefing series of titles. The practice assists foreign governments and MNC businesses develop an Asian strategy throughout their 28 offices across China, India, the ASEAN nations, Russia, and the OBOR countries, including research, due diligence, legal, tax, and operational advisory services. 2017 is the firm’s 25th anniversary. Chris is also the author of the well-received book “China’s New Economic Silk Road”, featuring profiles of all the participating nations as well as discussions and commentary on China’s OBOR plans. The Kindle version can be purchased for US$9.99 here. Chris may be contacted via info@dezshira.com or kindly visit the practice website at www.dezshira.com

|

![]()

Brexit Shows UK Has Turned its Trade Face Towards China, India, & the East

![]()

How the UK Can Benefit from China’s OBOR Ambitions

Dezan Shira & Associates and the United Kingdom: Country Brochure

Dezan Shira & Associates and the United Kingdom: Country Brochure

This year, Dezan Shira & Associates turns 25 years old in Asia. We retain extremely strong ties to the United Kingdom, employ numerous British nationals throughout Asia, and have serviced several hundred British companies in China and the Asian region at large since 1992. Explore Dezan Shira’s partnership with British investment in China in this brochure.

An Introduction to Doing Business in China 2017

This Dezan Shira & Associates 2017 China guide provides a comprehensive background and details of all aspects of setting up and operating an American business in China, including due diligence and compliance issues, IP protection, corporate establishment options, calculating tax liabilities, as well as discussing on-going operational issues such as managing bookkeeping, accounts, banking, HR, Payroll, annual license renewals, audit, FCPA compliance and consolidation with US standards and Head Office reporting.

- Previous Article Revigorer la Rust Belt chinoise : des incitations pour entreprises et expatriés

- Next Article China’s Investment Landscape: Finding New Opportunities – New Issue of China Briefing Magazine