Minimizing Online Supplier Fraud While Away from China

Many foreign companies, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), start their business in China without proper internal control mechanisms in place to mitigate the incidence of fraud. Lacking perhaps the resources or time required to implement appropriate controls, they tend to underestimate the risks of operating unprotected in this market. These risks have always been there, however, China’s tolerance of them has only increased during the novel coronavirus outbreak.

What does online supplier fraud look like in China?

The CFO of an international automotive parts manufacturer receives an alarming email from a junior accountant working at the Group’s Chinese subsidiary. The employee claims to have witnessed fraudulent activity perpetrated by the local General Manager for months and has decided to speak up.

The employee mentions important sales orders not being properly invoiced or recorded in the books, and feels he is being pressured into performing accounting fraud. Unconvinced yet still inclined to follow up on the whistleblower’s tip, the CFO decides to engage a third-party auditing firm to perform a review of the Chinese company’s financials.

The audit report reveals important transactions taking place between the company and private bank accounts opened in the General Manager’s name. An investigation of inventory movements reveals a significant mismatch between the value of the products shipped out of the warehouse compared to the company’s sales figures.

The Alipay account in question was linked to personal bank accounts opened in the General Manager’s name, and it turns out that the General Manager would only partially transfer back the monies to the corporate bank account, thereby successfully embezzling several million RMB undetected.

The above scenario is extremely common.

While it may not be possible to have complete oversight and fully eliminate all probability of frauds occurring, such cash theft can be prevented if the relevant internal controls are put in place within the organization.

Here are three ways you can frame your fraud prevention strategy in light of your relative risks.

Assess your specific risks, protect against fraudsters

Different companies are subject to different forms of fraud risks, depending on their industry, size, and business model. Companies need to make an assessment of their specific risks by identifying the areas where they are most exposed.

Small companies with a small China team should be concerned about the proper segregation of duties, for instance, with all things related to cash receipt and cash disbursement.

If the same person initiates and approves e-banking payments, or if one individual holds both the company chops and the corporate check book, there is a real risk of the occurrence of cash theft or fraudulent disbursements. Further, not separating the duties between the accounting and cashier functions opens the door for such economic crimes to go undetected.

Conversely, companies running large teams should carefully monitor the local payroll system, or otherwise risk being subject to fraudulent payroll and reimbursement schemes.

If the General Manager is colluding with or bypassing the HR team on payroll matters, he could conceive ‘ghost employees’ or fictitious bonuses to channel money to a personal bank account. If the headcount is large and payroll figures significant, it could be difficult to spot this form of fraud.

Likewise, opportunistic employees could take advantage of low individual supervision to utilize fraudulent reimbursement schemes: by overstating their work-related expenses, they could increase their personal remuneration.

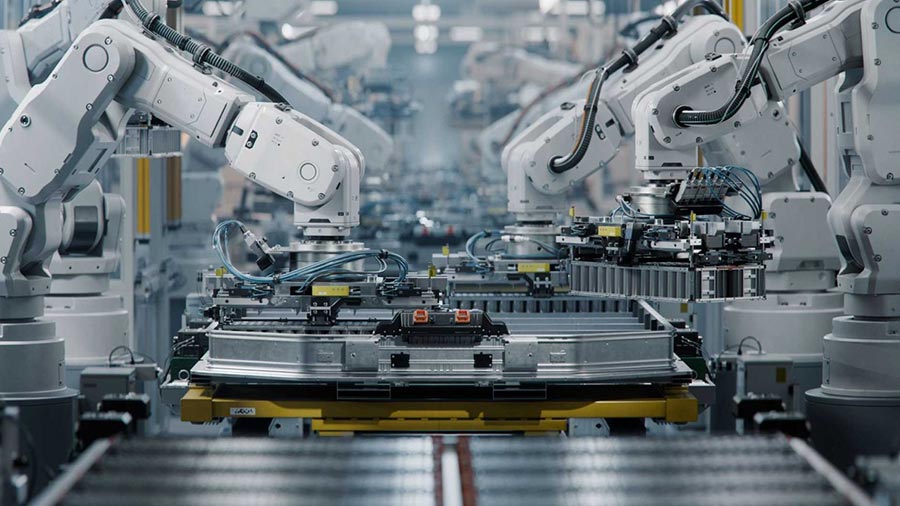

Trading and manufacturing companies performing sourcing activities in China should pay special attention to their supplier selection and management strategies. Indeed, such companies are prone to the collusion of their sourcing team with suppliers against the promise of bribes, or witness their local management select the companies of friends and relatives to act as suppliers. These examples of conflicts of interest are extremely common in China.

Companies that have not implemented IT systems to monitor and automate inventory management are most at risk. It then becomes extremely difficult to guarantee accurate consolidation between purchase orders received from customers, inventory movement records, and company accounting. We discussed specific IT issues during the coronavirus outbreak for foreign traders and investors in China in the article How Foreign Investors Can Leverage IT Systems in China During COVID-19.

Get familiar with China’s regulatory environment

Depending on the industry of focus, different companies may be subject to varying levels of scrutiny from regulators and should take this into consideration when designing their fraud-prevention programs.

Companies operating in China’s healthcare sector, for example, are more likely to be held to the highest of standards and face tough repercussions in the event of non-compliance.

Likewise, the Chinese F&B market is closely watched by regulatory bodies and foreign companies are particularly advised to strive for compliance. The aftermath of the melamine scandal in 2008 showcased regulators’ intolerance of non-compliance when public health and safety is involved, and the toughness of their sanctions when required.

Similarly, in recent years, many foreign food service outlets have realized the perils of operating without proper licenses, as illustrated by the large number of forced restaurant closures that have been occurring in Shanghai and other large cities around China. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic where tolerance levels to transgressions have been dramatically reduced.

The financial services sector is another industry subject to considerable scrutiny in China. While foreign fintech businesses rush into China lured by the promise of high rewards, many are reminded that PRC authorities intend to closely monitor how private firms are managing the savings of Chinese households. The crackdown on peer-to-peer lending platforms, as well as the recent fines levied on four major payment service platforms by the People’s Bank of China due to ‘irregularities’, are illustrative examples.

Localize compliance strategies

The regulatory environment in China is often quite different from that of the foreign company’s domestic market. It is therefore essential to understand the local specifics and assess compliance liabilities accordingly.

It is also important to bear in mind that PRC laws and regulations may be interpreted and implemented differently at the provincial or even municipal level. As such, companies operating in multiple cities across China are advised to localize their compliance strategies instead of adopting a uniform China strategy. We can assist – Dezan Shira & Associates has one of the largest footprints in China of any of the professional services firms – twelve offices on the ground in the mainland and one in Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, staying under the radar of regulators is becoming increasingly difficult, as Chinese regulatory bodies have become more integrated and coordinated.

An offense recorded by the tax bureau, for example, could raise the attention of other authorities such as the PRC Customs, the Administration for Industry and Commerce (AIC), or the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), etc.

Once an incidence of non-compliance is recorded, it can have a lasting impact on a company’s China operations, long after the company pays the penalty. The social credit system currently being implemented will only increase transparency and raise compliance risks. We discussed non-compliance with Chinese regulations and the impact that an investors’ social credit score can have upon their business in the article China’s Social Credit System Under COVID-19 Triggers Certain Obligations on Businesses in China.

Once the prevalent risks have been identified, stakeholders should work on the design of localized internal mechanisms to promote compliance and limit the incidence of fraud occurring at your China office.

Related Reading

- Terminating a Contract on the Grounds of Resume Fraud in China

- Inflicting Loss on Investors through Cooked Books: Assessing Accounting Fraud in China

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

We also maintain offices assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, The Philippines, Malaysia, and Thailand in addition to our practices in India and Russia and our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative.

- Previous Article Covid-19 Carriers: What Do China’s Wildlife Protection Laws Say about Pangolins?

- Next Article How to Enter China’s Online Gaming Market