Following Chinese State Policy? Then Invest In India

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, has been in Delhi the past few days looking to strengthen China’s interests in what appears to be a finally resurgent India. Wang’s meeting with his counterpart Sushma Swaraj, the Indian Minister of External Affairs, was one of the highest-profile exchanges in recent years, with Wang stating that the Sino-India relationship is “the most dynamic bilateral relationship with the largest potential in the 21st century.” For followers of business trends in China, looking to the statements issued by China’s leaders is often a good way to examine exactly what the Chinese government is thinking – when sentiments are positive, Chinese state money is usually quick to follow.

In the case of India, even prior to the recent election, China has been employing financial incentives to woo its leaders, offering to fund up to 30 percent of India’s total infrastructure development bill of US$1 trillion. But why the sudden desire to cozy up to India now?

Newly-elected Prime Minister Modi’s BJP Party has just won the first majority government in 30 years. Previously, he was Chief Minister of Gujarat, in North-West India, which bucked the national average the past decade and consistently posted annual GDP growth during this time of 10-12 percent. That sort of growth is similar to that achieved in Guangdong Province in China over the past ten years and is the primary reason why Modi was elected by the Indian people. Business-friendly policies combined with a majority government that can now push through much-needed reforms are a siren call to China.

Plus, the two nations have been very close historically – both are bordered by Tibet, and bilateral trade routes go back centuries. Chinese Buddhism came from India, and the Chinese epic “Journey to the West” is the tale of the Chinese Monk Xuanzang – a real historical figure – who made a pilgrimage to India. Although the story is embellished with characters such as the Monkey King and much magical goings-on – a sort of Aladdin for the Chinese – the “West” in the title specifically refers to India.

The two countries also have similarities in terms of modern history – China famously “stood up” under Chairman Mao following the rise to power of the Communist Party in 1949, while India gained its political independence from Britain two years earlier, in 1947. Both new states initially followed the Soviet model of central planning, and this mutual camaraderie extended well into Chinese social life – any Chinese national over 60 is deeply familiar with the old black-and-white Bollywood hits of the day, which were shown on Chinese state TV on almost permanent rotation. This mutual affection, however, was soured in 1962 after a brief border war that changed many relationships. Since then, both nations have regularly belittled each other and mutual ties were replaced by common mistrust. But this has already begun to change.

While it is true that China and India have ongoing border disputes, these have largely been left in a state of “agreeing to disagree,” far removed from recent Chinese spats with Japan, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Cultural exchanges have been improving, and although decades’ worth of negative spin-doctoring amongst their respective populations against the other may take some time to fade, ties are beginning to improve and popular interest is now on the rise between the two.

There is, of course, always an underlying reason for political reconciliation, and it is no different in the case of China and India: the two countries desperately need each other. This is not a common opinion among many China- or India-watchers, but for those of us who have a foot in both camps, it makes complete sense. Mutual trust and development between the two countries is only going to grow, and there are significant demographic dynamics at play to indicate this is the case.

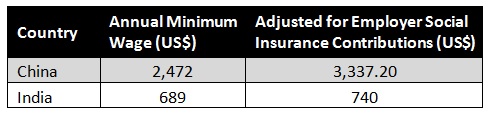

For example, while for the past 25 years China’s workforce has become the workshop of the world, this is quickly changing. Chinese wages are becoming more expensive, and its workforce is now aging and shrinking. A quick glance at the comparison below shows that the average Indian worker can now be employed for just 22 percent of the cost of a Chinese one.

India is also adding new labor to its workforce. With no one-child policy to contend with, demographics dictate that India will possess the world’s largest workforce by 2025, with about 900 million in the labour pool. Even today, the average age of an Indian worker is far less than in China – 23 years old against 37. As China’s workforce ages and declines, individuals will also have to support more family members. One Chinese worker (and his/her spouse) must support two sets of aging in-laws, pay for an education for their child, and shoulder increasingly expensive housing and living costs.

As a result, today China cannot afford to produce the cheap and readily-available everyday products that its aging population will need. Moreover, China’s middle class is set to boom, from about 250 million today to 600 million by 2020. They will demand the newest generation of iPads and iPhones (or their equivalents), and at reasonable prices. But China is now too expensive to provide these – this being the exact reason why Foxconn is relocating its entire manufacturing facilities to Indonesia (where China has also been funding huge amounts of infrastructure investment). The reality is that China must now ensure that its enormous middle class and graying population will be able to enjoy the benefits of cheap and easily available products.

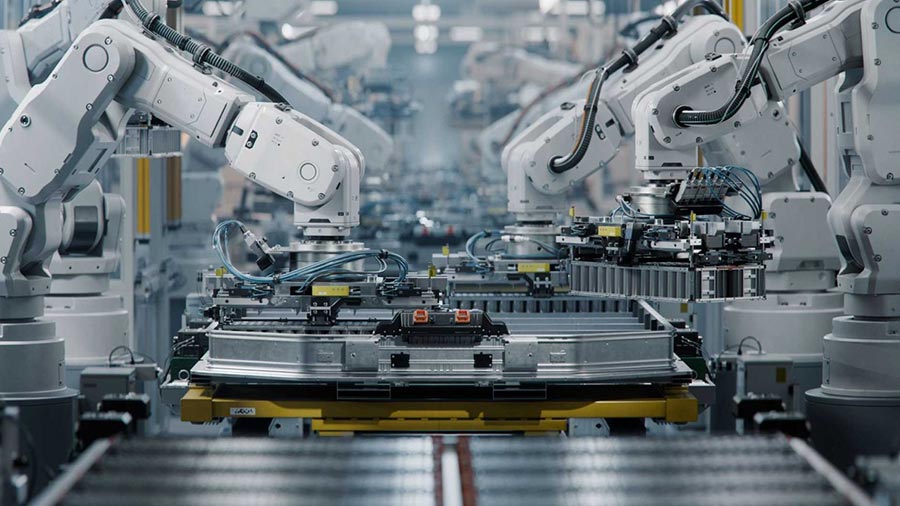

The only country that has the workforce able to cheaply deliver on the huge scale required is India. Therefore, getting India up to speed and producing mass-quantity, reasonable-quality consumer products is an absolute must for the Communist Party. Investing in India’s ability to provide China with cheap goods, while simultaneously pushing China’s own manufacturing up a few notches toward more innovative and hi-tech products, would be a win-win for both parties.

When China’s Foreign Minister states that “the Sino-India relationship is the most dynamic bilateral relationship with the largest potential in the 21st century” you can be sure he knows exactly the reasons behind that being the case. These are why China will invest billions in India’s infrastructure, and why the China-India trade corridor will become one of the most dynamic in the world. Both population demographics and China’s state policy dictate this will be so. And for those companies that follow Chinese state policy as indicators of future growth and opportunities, the signposts are all pointing West. To India.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates – a specialist foreign direct investment practice providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to alliances in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, as well as liaison offices in Italy, Germany and the United States. For further information, please email asia@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com.

Stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends in Asia by subscribing to our complimentary update service featuring news, commentary and regulatory insight.

Related Reading

An Introduction to Doing Business in India

An Introduction to Doing Business in India

In this guide, we introduce the basics of setting up and running a company in the country and some of the key issues investors should pay attention to. As India’s demographic sweet spot comes into focus, investors will find many opportunities to succeed in this exciting market.

Trading with India

Trading with India

In this issue of India Briefing, we focus on the dynamics driving India as a global trading hub. Within the magazine, you will find tips for buying and selling in India from overseas, as well as how to set up a trading company in the country.

New Indian Government Announces Economic Reforms to Induce Growth

India Becomes Second Largest Textile Exporter

India Sees Positive Trend as Service Sector Expands

- Previous Article Hard Economic Landing for Industrial China in Q1 2014

- Next Article Logistics, Warehousing and Transportation in China (Part 1)