Developing Global Free Trade: Linking China’s BRI with Mercosur, South America

(Part three of a five-part BRICS Free Trade Series)

Opportunities for China-based businesses in South America.

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Chinese President Xi Jinping has just returned from Brazil where he attended the annual meeting of the BRICS nations in Brasilia. With the Presidents and Prime Ministers from India, Russia, and South Africa also all attending, the scene has been set for Russia’s stint as the BRICS Chair in 2020, which is just six weeks away.

President Putin has stated that he wishes to use Russia’s Chairmanship of the BRICS grouping to further enhance its status within the UN. Meanwhile, the Brasilia Summit’s Declaration, agreed by all member countries, including China, states that the BRICS bloc had expressed common goals of “expanding trade and innovation”.

There are significant global trade issues to examine here: most notably exactly how such trade can be increased. At present, the BRICS countries represent over 3.1 billion people, or about 41 percent of the world population.

As of 2018, these five nations have a combined nominal GDP of US$18.6 trillion, about 23.2 percent of the global total, a combined GDP (PPP) of around US$40.55 trillion (32 percent of world’s GDP PPP) and an estimated US$4.46 trillion in combined foreign reserves. The IMF has projected that the BRICS nations will account for over 50 percent of global GDP by 2030.

Achieving that growth will require some planning and innovation on the part of the countries concerned. This can be reasonably expected to include advancing free trade agreements. To this end: China is a lead player in the Belt and Road Initiative, Brazil with its influence and membership in Mercosur is a leader in the South American region, Russia has a similar role in the development of the Eurasian Economic Union, India has a prominent role within the South Asia Free Trade Area (SAFTA), while South Africa is a major strategic partner in the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Where China differs is that unlike the other four members, it is not the primary member of a specific trade bloc per se, although it does of course have a number of important free trade agreements.

Although BRICS itself is not a free trade grouping, its prominence and intended actions almost certainly mean it is a platform for instigating just that – and the BRICS 2019 Brasilia Declaration expressed exactly this scenario.

In this series of articles, I will examine each of the possible scenarios that may occur in the development of free trade within the BRICS nations. Previous articles in the series are: Part One: Brazil, Mercosur and the Eurasian Economic Union and Part Two: India and the South Asia Free Trade Area.

In this article, I examine the potential for China’s engagement with the Mercosur bloc.

Mercosur

Brazil is the dominant member of the Mercosur Customs Union, which has as its current main members, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Mercosur operations involve free intra-zone trade and a common trade policy between member countries. It is the world’s fourth largest trading bloc after EU, NAFTA, and ASEAN, with an annual GDP of about US$5 trillion.

Mercosur is home to more than 250 million people and accounts for almost three-fourths of total economic activity in South America. It also includes Venezuela, but the country has been suspended from Mercosur since early 2016 for not complying with agreed tariff changes.

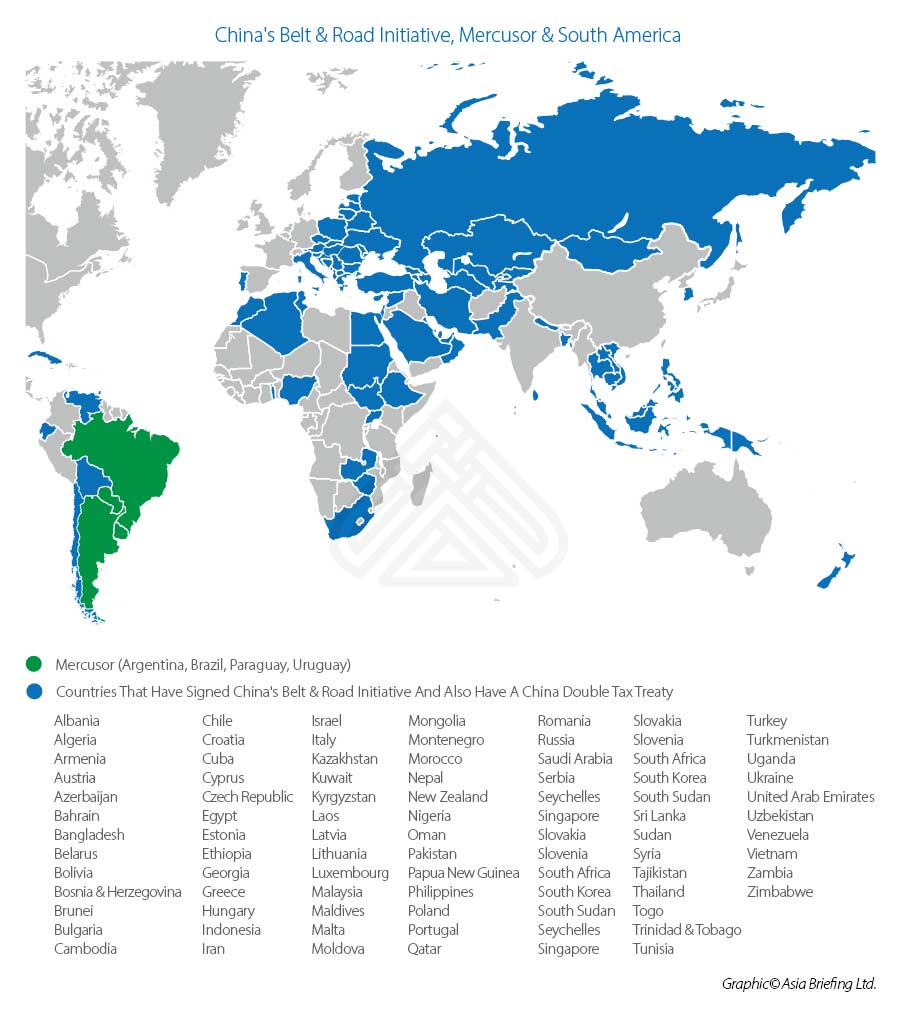

Associate members include the rest of South America, namely Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, and Suriname, along with Mexico and New Zealand as observer nations. Of these, China has double tax agreements with Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela, while an FTA with Colombia is still at the feasibility study stage. Mercosur Associate members do share some of the free trade benefits, although in several cases these are still awaiting legislative approval.

On enhancing Mercosur, however, Uruguay’s Finance Minister Danilo Astori said that “each Mercosur country should have a multiplicity of memberships. Mercosur must have joint international policies, an agreement on moderate protection from third parties and above all must have agreements with other trade blocs.”

Mercosur and China

For BRICS nations, developing free trade is beginning to come into effect. Brazil, under its membership of Mercosur, has a preferential trade agreement with India and another with the Southern African Customs Union. For China, however, although individual trade between Mercosur nations and China is increasing, very few have signed off on China’s Belt and Road Initiative – with Uruguay being one of the only major BRIC nations to have done so, signing off on an MoU in August last year at Montevideo.

China is Uruguay’s most important trading partner, purchasing 27 percent of Uruguayan exports. Uruguay wants to deepen that relationship by increasing cooperation in several other areas, in addition to trade, while offering attractive conditions for Chinese investors, particularly in the area of infrastructure.

Uruguayan Foreign Minister Rodolfo Nin Novoa, identified the following as key investment projects: Uruguay’s Central Railroad, a new fishing port, and rural electrification in the country’s north, and “expressed the hope” that Uruguay can serve as an “entry point” for China into the region, and help promote closer ties between China and Mercosur.

The fact that thus far, only Uruguay within the Mercosur bloc has signed off on China’s Belt and Road MoU showcases that there is still a lot to be done to “sell” the Belt and Road to South American governments. Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, not to mention the associate members, will also be watching closely as there are various issues. For example, China could become quite stretched with its resources in terms of providing finance and loans to governments in search of infrastructure funds, and has prioritized regions, such as Southeast and Central Asia and Africa, which are closer to home. South America, although undoubtedly rich in resources that China needs, will also be expensive. Infrastructure is poor, and the cost of opening that up is significant. One suspects that China is leaving its Belt and Road ambitions in South America for a later stage in its global development.

That said, China has been active in the pursuit of diplomatic ties. Is has formed the China-CELAC Forum, which brings China and the Community of Latin America and Caribbean States (LAC) together under a formal banner. The South American members of this include Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Paraguay, and Venezuela.

The China-CELAC Forum serves as a platform for dialogue and agenda-setting between international and regional leaders. It has become a Chinese priority as China pushes for deeper influence within the region and is considered by some to reduce the significant influence of the US on the politics and economics of Latin America.

China’s influence on the region has been accelerating fast. The value of trade between Latin America and China increased 22-fold between 2000 and 2013. China is LAC’s second largest source of imports, and the third largest market for LAC exports. China has recognized this in the second Chinese Policy Paper on LAC (2016), a cooperation trade network and investment review that leans towards the identification of energy and resources with new targets including the now Belt and Road construction, agriculture, manufacturing, and scientific and technological innovation. This fits in with countries such as Bolivia, Chile, and Peru, as their economic profiles are built on national mineral wealth leading their domestic and foreign policies.

That said, discussions are taking place between China and the Mercosur nations over upgrading trade relationships to free trade status. However, China does not seem to be in much of a hurry, preferring to want to arrange this on a “step by step” basis according to comments made by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi when meeting with the Uruguayan Foreign Minister Nin Ninova at the beginning of last year. Here, China’s “step by step” approach is probably an allusion to “one at a time” rather than a full China-Mercosur FTA. However, the Mercosur bloc is significant, being the world’s fourth largest with a population of 260 million and accounting for 75 percent of South America’s GDP. China’s trade with Mercosur totaled about US$107 billion in 2018.

China has already stated its intentions to double bilateral trade with South America to US$500 billion by 2025 and to increase total investment into the region to US$250 billion.

Of the South American countries that have signed off on China’s Belt and Road, Bolivia and Peru are being linked on the ground via improved rail connections, which allows mineral production from Bolivia to be exported to China through Peruvian ports. China’s Ocean Shipping (Group) Company (COSCO) appears to be facilitating this as it has purchased a 60 percent controlling stake in the Chancay terminal in the North of Lima for US$225 million. This is the first operation in Latin America for COSCO, which is already well known via its acquisition in the Greek Port of Piraeus.

China is also funding several major Argentinian infrastructure projects, including constructing two nuclear plants and US$2.5 billion spent on upgrading its main cargo rail network.

In Chile, China is providing an underwater Fibre-Optic network linking the two countries together. It will be the first underwater fiber optic cable to directly connect Asia with Latin America and will help drive interconnectivity, trade, investment, as well as scientific and cultural exchanges between the two continents. The cable begins in the Chilean city of Valparaiso, passing New Zealand, Australia, and French Polynesia to connect with Shanghai and beyond.

Ecuador joined the Belt and Road Initiative last December, and immediately agreed to a US$900 million loan from China, a further US$69.3 million for “reconstruction”, and received US$30 million in “non-refundable assistance”.

South American countries, which are similar to countries in Central America in that they have been excluded from trade with the US due to issues concerning minimum wages, may also start to turn its trade face more towards China. However, this will probably mean concessions will need to be made. China, who has already committed to providing significant financial and infrastructure resources to Africa, is chewing off two continents at the same time – a financial stretch even for Beijing’s pockets. The hot regional spots continue to be further north around the Panama canal, while at present it appears China is still evaluating where in South America the low hanging fruit is easiest reached.

Attention to when new free trade agreements with China are signed off in the next few years will provide the relevant clues. However, this doesn’t have to get in the way of trade. China is still a growing consumer market, and Chinese tourists are gaining more confidence in their international travels. South America may be some way off for the type and sheer scale of Belt and Road investments that have taken off elsewhere; however, an increasingly protectionist US and a resurgent China are changing the dynamics in South America. Attention to Chinese business practices and the opportunities that exist with both Chinese investments and China trade with South American businesses and especially those in Mercosur should not be underestimated.

To some extent, a Mercosur-China FTA deal then rides on the following points:

- An ability to link into China’s Belt and Road Initiative and expand Mercosur’s export range;

- Brazil’s political relations with Washington as opposed to Beijing; and

- The likelihood of additional free trade potential with other EAEU prospective FTA.

These are quantifiable points, although partially dependent upon the political landscape. Brazil, for example, currently enjoys good relations with the US and may not be so willing to upset Washington by seeming to develop trade ties with Beijing. Others points revolve around trade issues, such as China agreeing to tariff reductions, which will become more apparent over time.

Nonetheless, in the longer term, and given the huge network of Chinese free trade and economic zones emerging along the Belt and Road Initiative – including the Eurasian Economic Union and across Africa, closer study is warranted. This relationship is relevant as China has an FTA with ASEAN and with the EAEU (albeit one that is still subject to tariffs being negotiated), while Mercosur has an agreement with the Southern African Customs Union, meaning using Chinese facilities in these regions could be advantageous.

Benefits for Mercosur-based companies would be as follows:

- Access to Belt and Road Initiative Free Trade and Special Economic Zones to process/manufacture Mercosur origin products and goods for further export to ASEAN, African, and EAEU nations, in addition to China;

- Access to sourcing Chinese/ASEAN/African/EAEU products and goods for import back to Mercosur; and

- Mixing Mercosur/ASEAN/African/Chinese/EAEU products for final export to other global markets.

Clearly, product-specific examination needs to be conducted concerning the viability of such an arrangement, as well as the rules of origin and related product tariffs being understood. Nonetheless, there is enough substance between Mercosur, China, and their existing agreements to give credibility to the potential of such an alliance.

About Us

China Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Eurasia, including China, Russia, India, and the ASEAN nations, assisting foreign investors into the Eurasian region.

Through our membership of the Leading Edge Alliance, we also have partner firms throughout South America and have numerous South American clients in addition to a Spanish-speaking desk. Please contact us at asia@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com.

- Previous Article Indonesia’s Minimum Wage, E-Invoicing in Vietnam – China Outbound

- Next Article Developing Global Free Trade: China and the Southern African Customs Union