Britain Needs to Get Serious about Business with China and the Commonwealth

British Prime Minister Theresa May will visit Beijing this week to hold trade talks with British and Chinese business leaders about bilateral relations, trade, and the potential for participation in the Belt and Road Initiative. These actions take on additional significance as the UK negotiates its way out of its EU membership and needs to establish new trade routes under its own steam, and without the support of Brussels. It should be noted, however, that China-EU free trade talks have been stalled after years of discussions – leaving Britain the first among western European members to discuss a deal directly. This adds a higher level of ambition and potential to the upcoming China-UK bilateral discussions.

However, the UK is not entirely well organized at the business end of discussions. The long standing British Chamber of Commerce in China, which is supported by businesspeople and run for their benefit, boasts a couple of thousand members in China alone, and provided a concise voice for British business interests in China for decades. Curiously, it has been defanged. Problems began when a decision was made a decade or so ago to cease production of a British Chamber White Paper on UK-China trade relations. The official reason given was that as part of the EU, the European Chamber of Commerce in China would produce a White Paper on EU interests, including those of the UK, instead. In actual fact, the decision was taken to protect the interests of the British financial services industry, who could hide criticism of China behind an EU paper rather than be visible (and potentially singled out for punishment) in a British one. I was heavily against that decision at the time and made my views known that I considered it a selfish move that ran right over all other non-financial British business interests. Now, as we deal with Brexit, the UK will not be providing its opinions via the EU White Paper any longer, but also does not have one of its own either. We gave away a direct voice and connectivity link without really thinking things through.

Other issues have arisen concern the role and functions of the China-Britain Business Council (CBBC), an entity that is separate from the British Chamber. It traces its origins back to the “48 Group” – a collection of 48 British businesses who defied the UK government’s stance at the time and decided to travel to China to discuss trade with Mao Zedong. Catering largely for British MNC’s, its membership includes a few hundred companies, and is largely influenced by British civil servants, as it is supported by British government funding. Its accounts, however, have never been made public and it is unclear who actually benefits – though the suspicion has long been that certain people gain rather more from this than others – hence the secrecy over the accounting reports and details of what contracts and trade the organization has actually managed to accomplish. It also supplements its income with commercial services, placing it in the bizarre position of being a British taxpayer funded, commercial organization that competes with consulting firms and business centers. It is utterly inappropriately run, yet advises the British government on its China strategy.

![]() RELATED: China-UK Trade: The Effects of Brexit

RELATED: China-UK Trade: The Effects of Brexit

The British Chamber of Commerce and the China-Britain Business Council merged a few years ago, though kept their separate identities. However, with a larger, government-funded budget, and with civil service support, the CBBC has been taking the lion’s share of the spotlight, and has been directing and claiming success stories as its own. This is reflected in the state of the web views of each entity; the British Chamber website views have plummeted in the past two years, while those of the CBBC have risen considerably. The strategy has been to demonstrate the success of the merger, yet what it really shows is that the CBBC has effectively eaten Britcham.

This matters a lot in my opinion, as it means that British trade discussions with China are now dominated by civil servants rather than businesspeople. Another way of looking at it is to consider the role of Chinese State Owned Enterprises. In order to understand them, and negotiate with them, one always needs to keep an eye on the politics. The CBBC appears to have become the same – managed by civil servants dictating the political nuances of how British businesses should be positioned. That may be good for the bureaucrats, but the levels of a lack of transparency concerning the CBBC’s accountability are not that far removed from the lack of transparency within China’s SOE’s, and also functions to remove direct contact between British and Chinese businesses. It injects a permanent status of political thinking into trade and commerce. While that is fine, it is not always necessary or even desirable. Civil servants are not sources of wealth generation – businesspeople are, and the thinking is different.

It is a state of affairs I am not comfortable with, and I wonder what the end game will be. The CBBC is not transparent. If Britain is a true democracy, and upholds the standards of transparency in trade, then British businesspeople, rather than civil servants, should be leading the dance, rather than the civil servants. I do not believe this to be healthy. It is certainly not in the interests of smaller British businesses or British entrepreneurs, and one has to wonder what signals this sends to the Chinese.

However, the mandarins responsible for the CBBC and running the British Prime Ministers visit, with trade talks involved along the Belt and Road may have a political shock in store. China has of course institutionalized its Belt and Road project, and is diverting huge amounts of government resources into it. But Britain already has a similar entity that it to, could bring to the party – the British Commonwealth.

Now titled the Commonwealth of Nations (formally the British Commonwealth), the organization traces its establishment back to 1926. In reality, however, it is a loose arrangement between member nations of the then British Empire, connecting nations via London for the previous two centuries. Today, the body represents 20 percent of all global trade, and is headed up by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

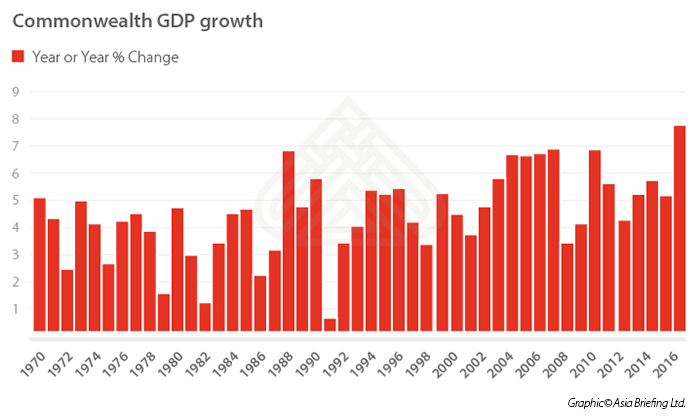

It may surprise many that the Commonwealth of Nations has been outstripping the EU in three determinants: population size, the size of the economy, and economic growth rate. The figures shown above are from material recently published by World Tracker as well as the IMF, World Bank, and United Nations.

The graphic below compares the Eurozone, EU, and Commonwealth from a market share of world GDP perspective, and shows the Eurozone and EU compared with the Commonwealth share of world real GDP.

This second graphic shows the GDP growth in the Commonwealth has accelerated over the post 1973 period in sharp contrast to the EU, where the growth rate has been falling gently from an average of 3.6 percent in the 1970s to 1.7 percent in the past five years.

The Commonwealth of Nations, collectively, is in rude health. What’s missing is the British government’s commitment to the Commonwealth of Nations as a driver for future UK growth and prosperity. This entails a great deal of negotiation and agreement between Commonwealth members, and especially for the legalities and trade issues concerning collective rights among members, in addition to the development of common systems. Such a task would be a bonanza for IT and e-commerce experts in the Commonwealth, and could bring tremendous rewards for Commonwealth members as a whole.

However, the Commonwealth of Nations is considered deeply unfashionable and almost persona non grata by many British politicians and civil servants today. That is an attitude completely at odds with what is happening in contemporary China and much of Asia, and is fast becoming outmoded in the modern era reshaping global diplomacy and politics. China, for example, has made giant strides in the last decade or so with its Shanghai Co-Operation Organization, a political, economic, and security organization that counts India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, and Uzbekistan as full members with China, as well as observer nations, such as Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia. Bangladesh, Egypt, and Syria have also applied for this status. Dialogue partners include Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkey, with applicants including Iraq, Israel, Maldives, Ukraine, and Vietnam. ASEAN, the Commonwealth of Independent States, Turkmenistan, and the UN are all guest attendees.

Russia, too, has its Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia and sits between China and Europe. The EAEU has the capability to bring Chinese goods right to the borders of the EU, and its trade has been increasing. In many ways, the EAEU effectively acts as China’s OBOR Free Trade Area, and especially so when its own negotiations with it come to fruition.

ASEAN is the Southeast Asian bloc comprising Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, and celebrates its 50th birthday this year. It conducts annual trade of some US$230 trillion. Five of the ASEAN nations have very strong historical connections with the UK.

There are several other examples, such as the Economic Union of West African States, the Arab League, and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), all of which contain countries with long standing ties to Britain.

China, meanwhile, has been re-inventing the wheel somewhat and has been active in promoting loose regional co-operative blocs, less formal in manner, but nonetheless useful. Some include EU members, such as China’s grouping of the 16+1, an informal European-China bloc that includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. This grouping even has its own €10 billion investment fund, known as the China, Central & Eastern Europe Investment Co-Operation Fund, based in Luxembourg. David Cameron, the ex-British Prime Minister, now heads up a US$1 billion Chinese Belt and Road Fund.

China has been motivating and incentivizing these nations to become prepared for new technologies and to act as a gateway for Chinese goods to enter Europe as well as for European goods to be prepared for the Chinese market. It is of interest to note, for example, that while Chinese-owned Volvo has announced it will only produce electric and hybrid cars from 2018 (a claim subsequently just taken up by Indian-owned Jaguar Land Rover), electric vehicle manufacturers in Romania and Bulgaria have recently been invested in by the new breed of Chinese auto investors. Volvo, meanwhile, remains a European brand – as does Jaguar and Land Rover with Britain. China is investing in and generating new technologies from Europe.

Going the other way, in terms of future trade, it should also be remembered that China has a market of close to one billion online consumers and a middle class of some 500 million. They want to buy. The country is also energy poor and agriculturally poor – China possesses 20 percent of the global population, but occupies just five percent of globally available arable land. This is why it has been developing its own trade institutions and initiatives to develop these, such as the Belt and Road Initiative.

The UK, therefore, could be on the right side of history, as long as it combines several development strategies together. They may not be historically happy or even currently politically correct; however, Empire was from a different nation to contemporary Britain. Hong Kong, signed off to the UK in 1842, has been a Chinese possession now for 20 years. That long-term China trade experience, deeper and more involved than that of most other nations, can be called upon in the spirit of free trade – after all, the Chinese aren’t getting anything out of the EU or the US right now. This, coupled with a British commitment to revitalize the Commonwealth of Nations, and bring those 53 member countries closer to China is a task that Britain alone is uniquely poised to provide.

The recent establishment and growth development of trade and dialogue blocs across Asia from ASEAN through to the EAEU, and the multilateral free trade agreements they have, and are about to enter into is, a way ahead. Britain has the Commonwealth of Nations, and a long history with China. It is unthinkable that Beijing today would stand idly by and let an asset such as the Commonwealth be forgotten and pushed out of sight. They would not, and their engagement in developing institutions and free trade illustrates the way ahead. In Britain, constructive debate on revitalizing the Commonwealth, mobilizing its members, and getting involved with Eurasia, should be the starting point for a new British manifesto for engaging with China, and the new emerging partners that come with the Belt and Road.

The CBBC, stuffed as full of civil servants as many of China’s own institutions, should be taking a leaf out of their book. Because if the Chinese owned the Commonwealth, you can bet they’d be doing something constructive with it, rather than let it fade away in a mere shadow of a long departed Empire. Theresa May, the FCO powers that be, and the British businesspeople concerned have a lot to do if they want to get on board. That means the strength and political will to restructure the CBBC, re-engage with the Commonwealth, and encourage a lot more practical business thinking than the current self serving lack of transparency that is currently being generated by British civil service platitudes.

|

About Us Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates, and a Visiting Professor at the Russian Higher School of Economics. The firm provides foreign investment market entry research, due diligence, legal establishment, tax, accounting and other professional advisory services to British and foreign businesses throughout China and Asia. Please email to china@dezshira.com or visit the firm at www.dezshira.com |

Dezan Shira & Associates and the United Kingdom

Dezan Shira & Associates retains extremely strong ties to the United Kingdom, employ numerous British nationals throughout Asia, and have serviced several hundred British companies in China and the Asian region at large since 1992. Explore Dezan Shira’s partnership with British investment in China in this brochure.

Establishing and Operating a Business in China 2018

China’s foreign investment landscaped changed significantly in 2017, where strategic investors will find that their options have broadened significantly. Establishing and Operating a Business in China 2018 is designed to explore the establishment procedures for the Representative Office (RO), and two types of Limited Liability Companies – the Wholly Foreign-owned Enterprise (WFOE) and the Sino-foreign Joint Venture (JV) – along with related business considerations that decision-makers should examine at the pre-investment, setup, and operational stages of the expansion cycle.

China’s New Economic Silk Road

China’s New Economic Silk Road

This unique and currently only available study into the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt examines the institutional, financial and infrastructure projects that are currently underway and in the planning stage across the entire region. Covering over 60 countries, this book explores the regional reforms, potential problems, opportunities and longer term impact that the Silk Road will have upon Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the United States.

- Previous Article Hong Kong BEPS Bill: New Transfer Pricing Regime to Regulate Documentation

- Next Article Hong Kong’s New Two-tiered Profits Tax