Setting Up a Practice in China – 20 Years Ago

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Jun. 12 – My firm, Dezan Shira & Associates, celebrates 20 years of operations in China this year. However, the landscape for establishing a professional services firm today, compared with 1992, is very different.

Dezan Shira & Associates is not, and never has been, a law firm – we operate instead as a “hybrid” practice specializing only in foreign direct investment. Within our permitted scope of business in China runs a whole array of services, many of which are not typically available to the average consulting practice without either years of proven experience or extended capitalization. Today, that scope includes the provision of services related to corporate establishment (filing of documents, obtaining license approvals, regulatory research, and so on) and then ongoing accounting, bookkeeping and tax advice. We also provide due diligence – both legal and financial, payroll (another addition to the scope of business, about to be enhanced by China’s CEPA regulations) and internal audit. It’s quite a mix, and almost certainly unique.

But 20 years ago, things were not like that at all. One should remember that this was shortly after the Tiananmen incident, and foreign investment in China had all but dried up. However, newly based out of Hong Kong where I worked for Asia Law & Practice and then Mossack Fonseca (which was a Panamanian law firm specializing in offshore corporate structuring), I studied both the new China publications AL&P had put out and spent hours poring over the only English set of Chinese regulations covering the setting up of representative offices (ROs), wholly foreign-owned enterprises (WFOEs), and joint ventures (JVs) in the entire Hong Kong library in Central. What struck me at the time was how regimented the process was – it made logical sense and was something I could relate to due to the structuring work I was involved with at the time for Hong Kong, BVI and other offshore-based companies.

Having previously visited China on many occasions, I decided that would be the place to be in order to begin offering advice on how to set up ROs and the like. Yet China at the time was not only an international pariah, it also had no effective legal code. Incredible as it may sound today, 20 years ago nearly all of the lawyers in China worked for the State. There were a select handful – and only a handful – of foreign firms operating in China back then. Coudert Brothers were a big player, as were Freshfields and Deacons of Hong Kong. Not all of the Big Four had obtained licenses either, and auditors, rather like the Chinese lawyers, also all worked for the State – mostly at the tax bureau.

Armed with my self-taught knowledge of how to set up ROs, I set myself down in Shekou, the deep water port next to Shenzhen, as it offered the lowest tax rate (12 percent) in China, and made applications to establish an RO. At the time, all legal professionals in China were known as “legally responsible persons” and impressed with my knowledge at a time (I had to sit an exam) when China was desperately short of any foreign talent whatsoever, I found myself with a Hong Kong company and an RO in Shekou legally able to provide corporate establishment advice.

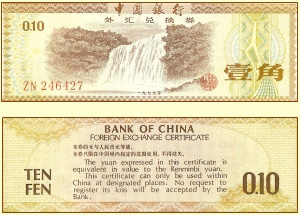

There were drawbacks – it was forbidden to have RMB (foreigners had to use the archaic and now long-since phased out foreign exchange certificates) while ROs had to be based in hotels. There were no commercial buildings available, at least not for foreign businesses, and the Chinese government felt the best way to keep foreign businesses under control and easy surveillance was to issue rules that meant many hotel ground and first floors in China were reserved exclusively for business offices and not for guests. You can still see this in some of the more remote and older Chinese hotel buildings today.

There were drawbacks – it was forbidden to have RMB (foreigners had to use the archaic and now long-since phased out foreign exchange certificates) while ROs had to be based in hotels. There were no commercial buildings available, at least not for foreign businesses, and the Chinese government felt the best way to keep foreign businesses under control and easy surveillance was to issue rules that meant many hotel ground and first floors in China were reserved exclusively for business offices and not for guests. You can still see this in some of the more remote and older Chinese hotel buildings today.

Did both myself, in terms of my abilities to practice, and those of my firm gain benefits and allowances through being so early in the China market? I would say almost certainly so, although that is a standard matter when an opening market requires expertise – concessions are given, and of course they were accepted. That certainly doesn’t mean it was any less hard work, even though such benefits are not available today. They remain legally valid, and it’s hardly my fault if other firms or individuals chose not to be in China when I was prepared to be there.

However, the relatively loosely defined legal environment and entitlements began to change. China liberalized the legal and accounting professions, and suddenly, almost overnight, a whole slew of privately-owned Chinese legal and accounting firms opened up. Dezan Shira & Associates predates almost all of them (Jun He, I believe, had been the first, granted a license as a trial). In fact, that move caused numerous problems for several years at many government departments, shorn of their best and brightest talent, most of whom had moved into more lucrative private practice. Government lawyers, tax collectors and auditors were very thin on the ground, leading at times to some very loose interpretations of the law and in many instances, the rise of the guanxi system between businesses and government.

Legally responsible persons in China, considered the Chinese equivalent of lawyers of the day, began to see themselves relegated to the sidelines of business administration as the Chinese legal profession began to take its first, early steps under the newly restructured Ministry of Justice. Nonetheless, I kept the role for some 15 years, stepping aside in 2006 as I began to spend increasing amounts of time outside of China in pursuit of business development in India and elsewhere. The role – which still exists – carries enormous responsibility, and individuals even today carry the full weight of the burden of ensuring their business remains in compliance with Chinese law. We have written about the contemporary role of the legally responsible person here, although 20 years ago it was far more encompassing, and often only reserved for professors.

Dezan Shira & Associates expanded (our very first client was a trademark registration for a pub in Shekou) and went from strength to strength. I had opened representative offices for the firm in both Shanghai and Beijing by 1994, and as the rules concerning the roles of foreign lawyers in China began to gain more shape, wisely took the choice to employ Chinese legal staff. Foreign lawyers are in fact prohibited from practicing law in China and expressly may not provide opinions on matters of Chinese law. Even today, that remains both strictly enforced and a bone of contention between China’s MOJ and the international legal community (we wrote about this recently here). Lawyers advising on matters of Chinese law must be Chinese nationals and must have sat and passed examinations set by the Chinese bar association.

The drawback with representative offices, however, was that they could not invoice, and this restricted operations and the ability to bill in RMB for many foreign practices and consultants until the late 1990s. China then began to liberalize the service sector aspect of WFOEs, although the capitalization requirements at the time were heavy – nearly US$250,000 (now they are a more reasonable US$15,000 or thereabouts). We were able to successfully apply for a WFOE license – still today held by our Shenzhen office – and closed all the old RO structures and replaced them with branches. I recall we were granted three years to pay off that capitalization requirement, although now it is even more than that.

Today, of course, Dezan Shira & Associates has grown both in size and in scale of operations. That Shenzhen WFOE has a large scope of business, and has expanded out to embrace another 11 branch offices. The practice, as is the case with all firms in China, is licensed and subject to annual reviews and inspections, in addition to audit, and we have passed every one since 1992.

Setting up a professional services firm today is far more regimented than it was back then, but the benefit of our doing so at that time – and as I said during a period when no one was willing to invest in the country – has been both the licensing opportunities and also the long-term experience it has provided us. I am sure that the route I was able to take back in 1992 could not be duplicated today, and there are people out there with lesser knowledge who may not be aware of that. However, rewards favor the brave, and the early bird in our case definitely did catch the worm in ways that are now off limits. Of course, that opportunity and regulatory environment had to be matched up with hard work and effort, a workable business model, and extensive marketing efforts, but I was able to solve these problems. Even today, both our practice and myself are regulated by the Chinese authorities and subject to laws that originated way back in 1992. We are subject to their jurisdiction and regulations, and remain so.

My role of course has changed since then, and I increasingly spend more time out of China. No longer the legally responsible person for several years now, I have instead taken the practice through the licensing and establishment procedures in India, Vietnam, and Singapore, with more Asian countries to follow. At present, I am still employed and pay taxes in China, but this year will also prove my last as I relocate to North America, and to sit in our U.S. liaison offices established last year. What began 20 years ago as some slogging through early books about China representative office law in Hong Kong – when many of today’s China expat lawyers and consultants were still in high school – has turned into a multi-national, multi-million dollar practice with 17 operational and 2 liaison offices spread across six countries. Hard work, diligence, and being early into the market when concessions are available are among the key components of success – not just in China, but throughout emerging Asia. And as the saying goes, every journey has to have a beginning, no matter how humble. Can my particular one be duplicated? Probably not.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the founding partner and principal of Dezan Shira & Associates, and established the firm in 1992. Since then, Dezan Shira & Associates has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States. Chris regularly contributes to China Briefing as well as our associated titles India Briefing and 2point6billion.com. The firm celebrates its 20th anniversary in November this year and will be hosting a series of commemorative events for clients and friends of the firm across China.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across emerging Asia by subscribing to the Asia Briefing weekly newsletter.

- Previous Article China Releases Comprehensive Measures for Evaluating Accounting Firms

- Next Article Opening a Bar in China – Without Licensing Laws