Reasons for Staying in China, and the Emergence of One Billion Consumers

The massive rise of Chinese middle class wealth brings the “one billion consumers” myth far closer to reality

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Part III of a three-part series:

- Part I: The China Conundrum – to Leave or to Stay?

- Part II: Reasons for Leaving China, and the Emergence of the Asia Century

- Part III: Reasons to Stay in China, and the Emergence of One Billion Consumers

Feb. 22 – The issue with any new, emerging market lies within a study of its demographics. In the early 1990s, China had plenty of young, energetic men and women that had just reached the working age, in addition to another generation behind them ready to do the same. The catch was that although the population of China topped over one billion people during this time, there was no middle class to speak of, and very little in terms of domestic consumerism. In fact, China continued to issue ration coupons to the entire population for commodities ranging from rice to oil until as late as 1992.

Consequently, foreign entrepreneurs that turned up in China 20 years ago to “sell to one billion Chinese” very quickly found themselves disappointed in the actual market conditions. However, the foreign entrepreneurs that did come to China to offer jobs and invest in the development of China’s infrastructure and in factories to manufacture export-quality goods to sell to countries with sizable middle class populations – such as the United States and Europe – did very well indeed. Over the past two and a half decades it has essentially been this business and economic truth that has dominated foreign investment practices in China. But this is now changing, and has increasingly been so for the past 10 years.

Over the past five years in particular, China has instituted a nationwide policy to upgrade the income levels of Chinese nationals in an attempt to spread that wealth around. The results to date have been erratic in terms of national income equality, but this gap will likely narrow after reaching a peak.

There are a number of reasons why Chinese nationals have grown wealthy, but not all of that wealth is sustainable. Unsustainable policies, such as the existing closure of China’s capital account, have seriously limited the amount of money that may be transferred out of China by Chinese nationals. Unlike most Western nations, China’s money is largely staying in China and much of the money has been invested in property. As a result, property prices have reached beyond reasonable levels in primary cities such as Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou, among many others. With nowhere to place capital and interest rates relatively low, property offers one of the only places to put cash, which pushes demand up, which raises prices…and so the dreadful cycle continues.

The capital account bubble in China is also manifesting itself in other ways, and with fancy cars now within reach, an explosion of high-end foreign automobiles, including Ferraris and Porsches, have begun to flood China’s streets. What were once global luxury brands have become relatively commonplace in China even despite the vastly inflated prices on such goods thanks to China’s luxury tax on these products. One wonders in fact what “luxury” or “status” means in terms of product value when sales volumes are so high. When a correction comes, it will be at this end of the market. So attention to detail as to how China proposes to manage its capital account and loosen the restrictions on Chinese nationals sending money overseas is crucial.

More sustainable for foreign investors in China is the opportunity to break into the middle class consumer market on a national basis. Again, this is driven by State policy as the government is keen to spread the wealth around. What this means is that a middle class consumer may aspire to purchase a Louis Vuitton handbag or a pair of Armani sunglasses in Shanghai or Beijing, but the desires in China’s second and third-tier cities (and even down to the fifth and sixth-tiers) amounts to owning a pair of Levi jeans or Nike shoes opposed to some no-brand local wear or canvas pumps. It means taking a date to Starbucks instead of a local café for tea, or buying Ferrero Rocher chocolates instead of the local variety. The dynamics of this discrepancy of latent Chinese consumerism is truly mind-boggling.

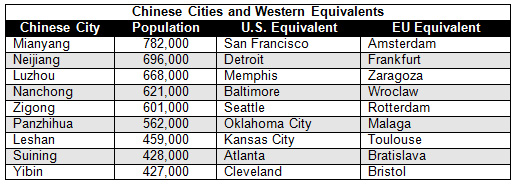

China has over 500 cities with populations of approximately 1 million, and we can examine a tiny fraction of these compared to some of their American or European counterparts (in terms of population) below:

My bet is that while many readers will be familiar with most of the American and European cities, hardly any will be familiar with their Chinese counterparts. There’s also one other aspect that I should point out: all of the Chinese cities mentioned above are in just one province: Sichuan.

What is happening in these lower-tier Chinese cities is that the local populations are now themselves becoming more affluent. Crucially, this is a phenomenon driven by State policy, as Beijing wishes to reduce the national income gap and raise the standard of wealth across the country by way of aggressive policies that increase minimum wages on a national basis (especially in the inland and central regions).

China has increased its national minimum wage by an average of 12.6 percent each year from 2008-2012, and there are no signs of this policy being altered anytime soon. These minimum wage increases have effectively increased China’s disposable income levels, and Chinese consumers are now moving from purchasing purely indigenous Chinese brands towards purchasing more expensive and well-known Western products.

Using the United States as a foreign investment case study in China, the past two decades have seen the pan-China establishment of a massive American sales platform right across the country. Brands such as KFC, McDonald’s and Starbucks have all introduced the concept of American quality and the American lifestyle experience that the bulk of Chinese consumers strive to attain. It’s a little known phenomenon because these brands are not considered “high-end” in the United States, but in China they really are a big deal.

The environment these outlets provide for the average Chinese consumer is one of a lifestyle upgrade in terms of exoticism, value, quality and entertainment. It is of significance that these brands are perceived as being representative of American values and are recognized as being U.S. lifestyle products, a factor that has enhanced the concepts of viability and trustworthiness of American products in China.

Let’s take a look at the consumer base these companies have already built and are continuing to develop on a national basis across China:

- Starbucks – Targeting to open 1,500 stores in 70 cities across China by the end of 2015

- McDonald’s – 1,600 stores already opened by the end of 2012, and a total of 2,000 stores spread across 150 cities are planned to be opened by 2013

- KFC – 4,000 outlets currently open across more than 650 cities in China. Currently opening at a pace of one new outlet per day

With a development platform such as this on which to base the acceptance of American products and quality, I predict a huge surge over the next decade for middle market global brand exports to China. The development of these consumer outlets represents a great opportunity for other global manufacturers to build on what has already been achieved here and also provides a fairly large Chinese consumer market base already familiar with the Western concepts of value, quality and consistency – issues that China’s domestic brands have largely failed to emulate.

The Louis Vuitton bag may still represent the pinnacle of having made it as part of China’s super wealthy in Shanghai, but in cities such as Mianyang, the youth are looking to trade up from their cheaper Chinese sports shoes for Nike sneakers and upgrading their wardrobe with Levis jeans.

These consumer patterns being replicated throughout China’s inland provinces means that the time to invest in – or stay in – China to take advantage of the massive surge of middle class consumerism is now. This trend will likely continue to happen for the next two decades on a national basis, and entrepreneurs now truly have the ability and chance to “sell to one billion consumers.” The time to sell to China has arrived, and now is the time to be looking at doing so. Despite the difficulties export-driven manufacturers face, conversely, international business wanting to sell to China are on the cusp of a sales bonanza.

In summary, the key to understanding China’s potential – and downside – lies within each individual foreign investor’s business model. Manufacturers looking for cheap labor and land are better off now considering Southeast Asia, while international companies with products to sell should be looking at China and getting over here fast – because if you don’t, your competition will.

Finally, is it possible under today’s global trade circumstances to both have your cake and eat it too? Right now, the answer is yes. Cheaper manufacturing can be found elsewhere in Asia, and China now has the means and desire to buy. For global business executives, there has never been a better time to be in both China – and Asia.

Part III of a three-part series:

- Part I: The China Conundrum – to Leave or to Stay?

- Part II: Reasons for Leaving China, and the Emergence of the Asia Century

- Part III: Reasons to Stay in China, and the Emergence of One Billion Consumers

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the founding partner and principal of Dezan Shira & Associates – a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email china@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download the company brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across Asia by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.

Related Reading

Expanding Your China Business to India and Vietnam

Expanding Your China Business to India and Vietnam

The March/April issue of Asia Briefing Magazine discusses why China is no longer the only solution for export driven businesses, and how the evolution of trade in Asia is determining that locations such as Vietnam and India represent competitive alternatives. With that in mind, we examine the common purposes as well as the pros and cons of the various market entry vehicles available for foreign investors interested in Vietnam and India.

Trading With China

Trading With China

This issue of China Briefing Magazine focuses on the minutiae of trading with China – regardless of whether your business has a presence in the country or not. Of special interest to the global small and medium-sized enterprises, this issue explains in detail the myriad regulations concerning trading with the most populous nation on Earth – plus the inevitable tax, customs and administrative matters that go with this.

Doing Business in China

Doing Business in China

Our 156-page definitive guide to the fastest growing economy in the world, providing a thorough and in-depth analysis of China, its history, key demographics and overviews of the major cities, provinces and autonomous regions highlighting business opportunities and infrastructure in place in each region. A comprehensive guide to investing in China is also included with information on FDI trends, business establishment procedures, economic zone information, and labor and tax considerations.

China Becomes World’s Largest Trading Nation, Passes United States

How To Sell To China – The Initial Evaluation Process

- Previous Article Reasons for Leaving China, and the Emergence of the Asian Century

- Next Article China Releases Intellectual Property Plan for Strategic Emerging Industries