The China-Angola Partnership: A Case Study of China’s Oil Relations in Africa

By Shelly Zhao

May 25 – Following our other recent articles concerning Sino-African oil relations and the role of Chinese national oil companies (NOCs), this article in our China-Africa series takes a look at the case of Angola, China’s largest source of oil in Africa. Oil is at the crux of the Sino-Angolan relationship and a main driver of China’s expanding relations with south-central African country. Major aspects of relations between the two countries are China’s loans in exchange for oil as well as involvement in Angolan infrastructure.

May 25 – Following our other recent articles concerning Sino-African oil relations and the role of Chinese national oil companies (NOCs), this article in our China-Africa series takes a look at the case of Angola, China’s largest source of oil in Africa. Oil is at the crux of the Sino-Angolan relationship and a main driver of China’s expanding relations with south-central African country. Major aspects of relations between the two countries are China’s loans in exchange for oil as well as involvement in Angolan infrastructure.

Angolan economic recovery and oil

After struggling for over a decade, Angola gained independence from Portugal in 1975 and lapsed into a long civil war that lasted for 27 years until 2002. Since the end of the war, Angola has focused on postwar reconstruction and has made great strides in the development of its economic, largely propelled by oil. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Angola had an average GDP growth rate of 10.5 percent between 2006 and 2010 and although the country’s GDP was adversely affected by the Global Financial Crisis, it appears to be on its way to recovery.

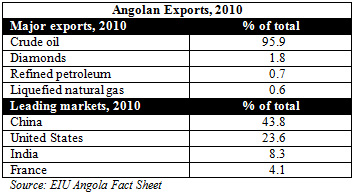

Angola’s main exports are oil, diamonds, coffee, timber, and other mineral resources. The country joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries in 2007 and since 2008 Angola has been the top oil producer in Africa. In 2009, oil comprised 85 percent of GDP, 95 percent of exports, and 85 percent of government revenue. The majority of its revenues come from oil and diamond exports, and the majority of oil production is concentrated in Cabinda Province.

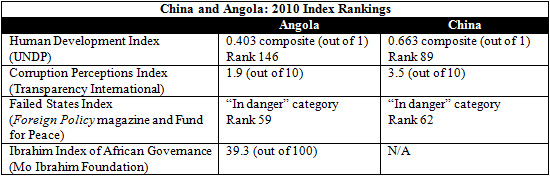

Angola’s state capacity remains limited, and organizations like the World Bank have recommended institutional reform of the oil and diamond sector. Poverty, corruption, lack of transparency, lack of infrastructure, and economic inequality issues continue to challenge governance and question whether economic growth can bring economic development benefits. With political power still centralized and the new constitution in 2010 further postponing elections, the process of Angola’s democratization remains in question. Below is a snapshot of Angola’s rankings in different development indices (with China for comparison).

Angolan oil

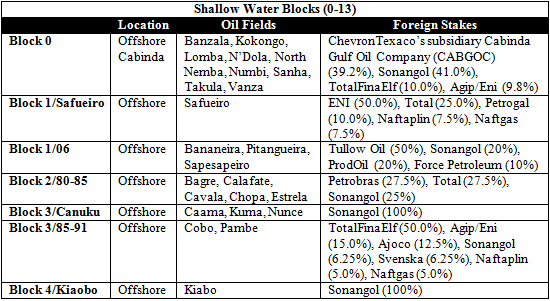

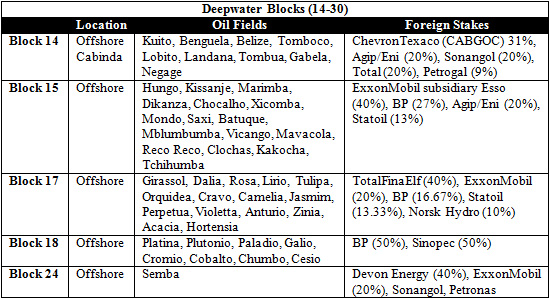

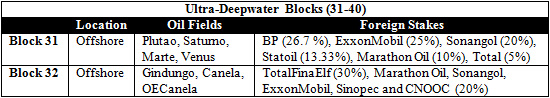

Oil has become crucial for Angola’s government revenues and economic growth. Created in 1976, Sonangol Group (Sociedade Nacional de Combustiveis de Angola) is Angola’s powerful state-owned oil company that oversees the production of oil. Sonangol mainly cooperates with international oil companies through joint ventures and production sharing agreements. Africa’s offshore oil is divided into 76 blocks, of which 35 are active. The following tables below show the oil companies’ stakes in some of the important oil fields. Block 0 and Block 15 make up the majority of Angola’s oil production.

China and Angolan oil

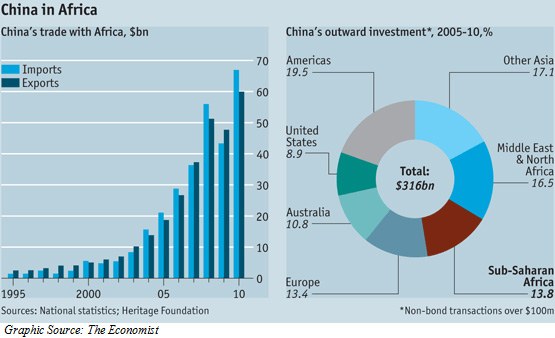

Chinese and Angolan economic and political ties expanded during the late 1980s, with the signing of their first trade agreement in 1984 and the establishment of the Joint Economic and Trade Commission in 1988. Since then, bilateral trade increased steadily and jumped from 2005. In 2010, bilateral trade exceeded US$120 billion and Angola is currently China’s largest African trade partner.

The single most significant commodity for the Sino-Angolan economic relationship’s expansion has been crude oil. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, crude oil still composed over 95 percent of Angola’s exports, and China remained a significant player.

As the previous section shows, Western international oil companies (IOCs) still retain the biggest stakes and most operational rights in Angolan oil fields. Among the largest players are ChevronTexaco (U.S.), ExxonMobil (U.S.), TotalFinaElf (France), BP (UK), and Agip/Eni (Italy). Even so, Chinese NOCs have gained somewhat of a foothold in Angola. China’s oil deals with Angola are characterized by loans and credit lines in connection with infrastructure projects. There have been three major multibillion-dollar deals through China Eximbank:

- 2004: US$2 billion line of credit

- 2005: US$2 billion loan in exchange for oil; in 2006 China added US$1 billion more

- 2007: US$2.5 billion line of credit

In the Angolan oil blocks themselves, Chinese presence and activity includes:

- Block 3/80: In 2004, Sinopec sought to gain production rights in Block 3/80. Sinopec’s bid included a China Eximbank US$2 billion line of credit offer. This helped to sweeten the deal, and Sonangol decided in favor of Sinopec and did not extend Total’s license.

- Block 14: Also in 2004, Sonangol and Sinopec established a joint venture, Sonangol Sinopec International Ltd., through which they cooperate on oil production and refinement. Their activity also extends to Blocks 15, 17, and 18.

- Block 15, 17, 18: Sinopec and CNOOC gained exploration and production rights in these blocks, in cooperation with Sonangol as well as foreign IOCs.

- Block 18: Sinopec currently owns a 50 percent stake in Block 18, which it purchased for US$2.46 billion in March 2010 (see China Briefing’s analysis).

- Block 32: In 2009, CNOOC and Sinopec purchased a 20 percent stake in Block 32 from Marathon Oil Corp for US$1.3 billion.

Perspectives on China in Angola

China’s presence in Angola presents a fascinating case study of China’s oil relationships with African nations, and there is a complex interplay of benefits and challenges. In Angola, China’s presence remains modest relative to that of the Western IOC giants. However, beyond the percentage share of stakes, China’s loan-for-oil deals with Angola represent its growing reach and point to many intangible ramifications. China’s loans are an attractive alternative to those from international institutions that can have democratic-promoting strings attached. One common criticism is that China’s economic policy is resource-driven and goal-oriented; its means-to-an-end, non-interference approach can thus challenge Western countries’ hopes for democratic progress in Angola.

A fundamental question is whether moral responsibility is part of the equation, or whether oil deals are business transactions in essence – one exchange for another. Another is what kind of balance is preferable between Angola’s economic growth and economic development objectives.

These perspectives can be useful for assessing the lens through which observers view China’s Angola policy. There is little doubt that an increase in Angola’s GDP output is necessary to increase its standard of living, but oil-rich countries – Saudi Arabia and Oman, for example – that experience “windfall gains” from oil may need more time to adjust.

Thomas L. Friedman’s “First Law of Petropolitics” posits an inverse relationship between the price of crude oil and the pace of freedom. Yet China also provides Angola with much-needed infrastructure construction, at the opportunity cost of possible transparency and corruption improvements often required of International Monetary Fund assistance. Ian Taylor has remarked that Angolan elites are “deeply appreciative of China’s ‘non-interference’ stance.” Comparatively speaking, the low-interest, condition-free, and infrastructure-friendly Chinese loans remain attractive to the Angolan government.

From Angola’s side, analysts note that the Angolan government also wishes to diversify both its exports and its trade partners. A 2007 Chatham House paper “Angola and China: A Pragmatic Partnership” found that the African officials interviewed wished to avoid overdependence on China as an economic partner. The Angolan government has also expressed this publically. For example, in 2008, Angolan President dos Santos remarked on the country’s economic relationships that “globalization naturally makes us see the need to diversify international relations and to accept the principle of competition, which has in a dynamic manner, replaced the petrified concept of zones of influence that used to characterize the world.” The People’s Daily also reported that the Angolan Trade Minister Maria Idalina Valente said in January 2011 that Angola’s biggest challenge is diversification of its economy beyond oil.

The Sino-Angolan oil relationship will likely remain significant and sustained for the coming decades. Yet it is important to avoid overstating China’s presence in Angola and to conclude that an increase in Chinese NOC activity means “crowding out” the IOCs in Angola. Principal-agent or neo-colonial conclusions of the bilateral relationship can overlook the two-way processes, as the Angolan government continues to bear in mind its relationship with China in context with its global economic partnerships and its long-term development. If the previous decade is any indication, China will continue to seek larger stakes in Angola’s oil sector, and both countries seem to favor the oil-for-infrastructure quid pro quo arrangement at present.

Related Reading

China’s Energy Strategy and the Role of Gov’t Oil in Africa

The Geopolitics of China-African Oil

China Goes to Africa as New Dynamics Emerge

Africa to Get US$10 Billion in Loans from China

China’s Africa Strategy Blossoms as Relationship Develops

- Previous Article China-Vietnam Business Update: May 24

- Next Article U.S. Study Mission Discusses China’s Inflation, Living Costs and the Conspicuous ‘Housing Bubble’