The Current Business Environment on the Ground in Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s politicians and business community need to step up and start to take responsibility for its own future

Op/Ed by Alberto Vettoretti and Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Recent images of protests and public disorder in Hong Kong have been beamed around the world, portraying the city as being in complete turmoil due to the Legislative Council (LegCo) attempting to pass a law that would allow the repatriation of Hong Kong citizens to mainland China in the event of criminal proceedings taking place there.

In terms of all the furor about the treaty, it should be noted that the extradition process is not automatic: an extradition treaty needs to be sent to the Hong Kong government, and is then subject to judicial review. Extradition to China applies to criminal elements who have committed crimes on the Chinese mainland, not in Hong Kong. It is also bilateral: criminals committing crimes in Hong Kong who then run away to China can also be repatriated to face trial.

So what is going on concerning the resistance against the bill?

Our firm has had an office in Hong Kong since 1992, way before the handover of Hong Kong to China, and we know the city well. In terms of business practicalities, the practical disruption to most of Hong Kong (but not the immediate Central-Admiralty area, which is where LegCo is based) has been limited. Our offices are in Tsimshatsui – just one metro station ride away – and it has been quiet. However, staff living in the immediate vicinity around Admiralty (as well as others operating from offices in the affected area) were given a few days off work as roads were blocked, traffic disrupted, and it was hard to navigate the immediate streets. Most companies in that situation gave their staff the choice to work from home.

In terms of what has driven the mass discontent, it is important to understand that the extradition bill is just a spark that lit a bonfire of pent-up unhappiness. The reality is that the recent protest is just the tip of the iceberg; the root of the problem has older origins. Local politicians have become distanced from the actual lives of the Hongkongers they are supposed to be serving under the “one country, two systems” framework. These problems – which are numerous – are as follows.

Decline of Hong Kong’s competitiveness

Hong Kong has been losing steam in term of competitiveness for some time: from the affordability of housing to the ease of doing business. It is a challenge to open a bank account and more could be done to create a nurturing business environment. More could also be done to engage the youth, and define career directions besides finance and re-exporting. Larger companies can still afford to set up shop there, but foreign SMEs are now entering the Hong Kong market at slower rates. There is full employment, coupled with stagnating salaries. Meanwhile, living costs are increasing.

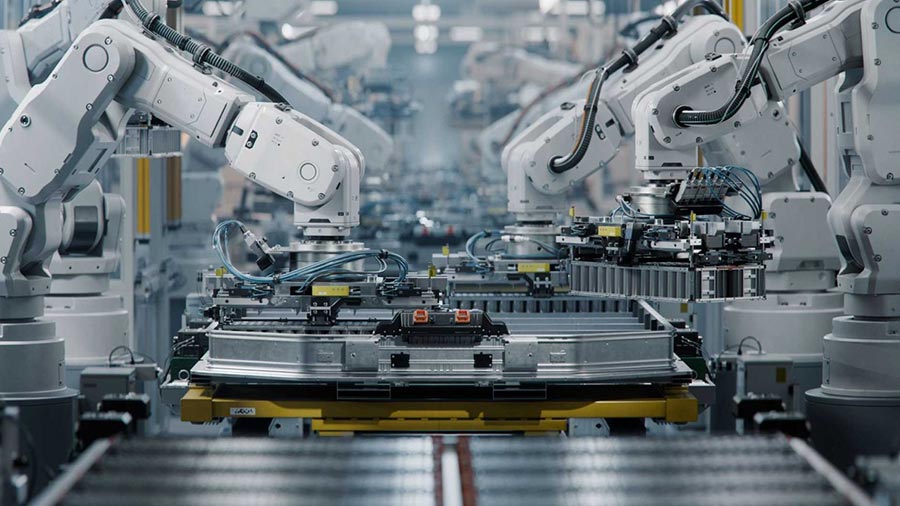

Lack of investment in new technologies

Hong Kong is not an advanced digital economy, and it is becoming more bureaucratic – business and administrative processes remain manual and there are no digitalization processes in the government. Hong Kong missed the digitalization train, and this means the territory will slip even further in ease of doing business rankings and its attractiveness to non-finance, non-Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, it takes more than 30 days to de-register one employee from a company and re-apply for a new work permit in another. The application process is manual, meaning travel, appointments, and waiting in queues in government offices. There is no ability to carry out the process online, and this is the case with most other processes too.

Too much business lobby interference

Hong Kong has developed a huge number of lobbyists, creating massive roadblocks in the decision-making process as everyone jostles to promote their own agendas. Hong Kong’s taxis are the most obvious example on the street: the government missed the “go green” vehicle movement; diesel fumes make the busy city areas uncomfortable; the vehicles are old Toyotas; competition in the form of Uber was killed off; payments for tolls still often need to be made in cash.

Bureaucracy has overtaken Innovation

The Hong Kong government has reverted to being bureaucrats with no say in their policies. A lassez faire attitude of resisting attempts to change or promote alternatives is prominent, because of either existing interests or fear of doing something that could eventually backfire. This means important development decisions are not taken or postponed, and Hong Kong is losing competitive ground.

Inability to adapt to a changing regional environment

There is also a changing landscape for Hong Kong. In the years since the territory reverted to China, many foreign countries, and even entire Asian trade blocs, such as ASEAN, have new, DTAs with China, and other countries in the region.. With the new compliance requirements and transparency needs of offshore jurisdictions, Hong Kong has also lost the appeal as an outsourcing center for businesses. These are natural evolutionary developments. But the Hong Kong government has not moved to change anything, take up new technologies, or consider changes benefitting new foreign investors in the Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with China. Nothing is being done to plug the gap inevitably left by changing technologies, business laws, and regional trade agreements.

Lack of business diversity

While FDI into Hong Kong is still substantial at over US$110 billion in 2018, the majority of this money goes into investments, the stock market, and real estate. The main sources of FDI are actually offshore (the British Virgin Islands and other offshore jurisdictions) so the real source cannot adequately tracked (in turn making monitoring of trends difficult); however, most is assumed to have Chinese origins. In fact, it is Chinese cash that is keeping Hong Kong afloat. Whether that is good for the economy and a long-term strategy is debatable, but this is currently not being adequately addressed by local bureaucrats.

Over-reliance on tax as an incentive

Hong Kong’s taxes are still low (the profits tax is 16.5 percent); however, taxes are coming down in the Asian region anyway. Selling a low tax jurisdiction is not enough to make Hong Kong attractive. An example of this is the low individual income tax offered to attract foreign talent into nine mainland cities in the Greater Bay Area. The 15 percent rate offered to foreign talents working in the nine mainland cities in the Guangdong province is as low as Hong Kong’s existing rate, which may challenge Hong Kong’s tax advantage. Individuals don’t usually make decisions on where to work – corporations do. The list of incentives offered to attract talent into the Greater Bay Area is therefore not sufficient in and of itself.

Lack of social measurements on the ground

These varying issues have unified – although this would not have been the intention – to create a huge divide in Hong Kong society. This is not a recent phenomenon. The recent protests are indicative of the fact that the average local Hong Kong youngster does not really see much hope or future in Hong Kong. In polls, Hong Kong’s youth regularly count as among the unhappiest globally, while mature Hong Kong society is not that far behind. It is hardly surprising that this has led to tensions and movements getting out of control.

Real estate issues

There is a tendency abroad to believe that Hong Kong equals the Central district so often seen on TV; however, this area comprises less than 3 percent of the population. The remaining 97 percent is also under pressure. An average of 70 percent of total income goes to paying off mortgages, meaning the government cannot afford to cool the market too much. Real estate costs continue to increase, property developers build ever-smaller apartments, and people continue to invest in what are becoming shoeboxes, while the government continues to make money from the stamp duty. Meanwhile, multi-millionaires with no connections to Hong Kong buy up the medium to high-level real estate. It is unclear how long this can continue. Singapore showed an alternative many years ago in its successful Public Housing scheme, and enforced social payments into it. There were complaints and some initial snobbery against living in these developments. Yet, now some of those buildings are extremely valuable. Singapore consequently has a home ownership ratio of 91 percent. Hong Kong has a ratio of 49 percent. It remains the main social situation behind the local unhappiness, and one that Hong Kong’s politicians and real estate developers have consistently failed to deal with.

Lack of planning on the education sector

There are also challenges in the education sector. Despite having five universities in the top 100, our opinion is that Hong Kong is not developing the right type of skillset, or attracting the right skills into the market. Highly paid professors, meanwhile, are another lobby group. Local Hong Kong students also do not want to move to China; the cultural divide between Hong Kong and mainland Chinese students remains wide.

Exaggeration of Hong Kong’s past

There are local issues too. China has thrown a (sort of) life-buoy to Hong Kong with the Greater Bay Area integration initiative. However, many are stuck in the past, making it more difficult to accept that things are different now. That hasn’t been helped by the city eradicating some of its history – by removing old British artifacts such as the red pillar boxes, there is now an emotional desire to see them again.

Hong Kong then has a multitude of problems to deal with. Hong Kong still markets itself as a ‘Gateway to China’. That is outdated and has been ever since foreign investors were allowed to set up in China directly. This situation is a combination of vested interests, greed, and lack of technical capabilities. If anything, the local protests against LegCo show that the real anger is directed at local politicians and lobbyists, and less towards Beijing.

There are steps that can be taken. It is clear the housing situation is a major source of concern. Hong Kong needs to stop the development of ultra-small apartments and cap the high prices being asked for them. There is plenty of land in Hong Kong. Real estate developers need to be controlled in ways that serve people’s needs, not the other way around.

In terms of business, which is the aspect we can claim some expertise over, Hong Kong needs to devote huge amounts of money to play catch up in its digitization. Some of the aspects in which ordinary commerce has to be conducted are not competitive. A government mindset seems to have assumed that 2008 was a good year and that all that needed to be done was to maintain the status quo ever since. Hong Kong needs a new development plan with educational support to develop technical capability – and the Hong Kong youth, protesting outside LegCo, understand and recognize this.

Other developments could reenergize Hong Kong’s position as a conduit for China. Much has been made of the CEPA that has been hugely beneficial for Hong Kong companies doing business in China. Yet it is outdated in terms of what it provides, prejudicial against foreign investors, and subsequently needs review. A CEPA document that made it easier for foreign investors to qualify would prove a boost to the local economy in terms of bringing back foreign SME investors, and subsequently, to China.

The messages are quite simple. Hong Kong needs to take some responsibility, and talk things through with Beijing. To date, and Chris has seen this directly, Hong Kong’s leaders tend to go to Beijing to lobby for agreement on self-serving business deals, rather than what the territory needs for its future development. This situation needs a radical overhaul, and fast, and those innovations and commitments need to come from LegCo to make it happen. The self-serving pawning over asking for immediate business gains from Beijing needs to stop now, and be replaced with strong, innovative, and energetic dialogue concerning Hong Kong’s real needs for the future.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia and maintains offices in China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Russia, and Vietnam. Please contact info@dezshira.com or visit our website at www.dezshira.com.

- Previous Article US and China Agree Trade War Truce After Xi Puts His Foot Down

- Next Article India’s Import-Export Trends, Vietnam’s New Competition Law – China Outbound