Chris Devonshire-Ellis on Art and Culture in Understanding China Business

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Jul. 28 – An important, but oft neglected or ignored aspect about conducting business in China – and especially when one is in a position of consulting foreign investors, as our practice Dezan Shira & Associates is, involves getting across to clients the importance of understanding or appreciating China’s culture. It’s that extra component that represents added value to a new-to-China investor, and can manifest itself in many ways.

A lawyer, accountant or consultant familiar with China with several years of on-the-ground experience will have developed his or her own circle of contacts, practical expertise and a “feel” for China that individuals and firms not in-country simply cannot match. A “second sense” tends to develop over whether or not a particular investment may or may not be a good idea, relationships (despite the naysayers, guanxi always exists) can be of assistance either directly or for asking advice, opinions or introductions, and a platform of “China security” exists for those who really do breathe the air, eat the food, speak the language and essentially, walk the walk. It’s a situation that all expatriates in China will appreciate. When they look back at what they’ve learnt in their years of being in China, there is no comparison, while firms and consultants based overseas just do not have that added “China” value.

Advice about investing in the United States, for example, would not be sought from a law firm in Germany. It’s nonsensical. Likewise, advice concerning China is best answered by those with a China presence, and there are many good local and international firms operating in China nowadays for the investor to choose from without needing advice from the inexperienced. If your consultant isn’t prepared to live or be based in China, then why should you listen to his advice on setting up there? The cultural aspect and local China sensibilities just have to be in place. If they’re not, and advice is dispensed externally from China, that lack of knowledge and resources will equate to poor or inaccurate advice.

At our China Briefing subsidiary, we’ve always tried to get across the cultural aspect of doing business in China and have taken up this challenge both through easy to read articles and the provision of on-the-ground commentary, and have gone a stage further with our monthly magazine. For the past three and a half years, China Briefing Magazine has featured covers from contemporary Chinese artists. Looking at the covers of other business publications, they all seemed rather dull, pictures of men in suits, the ubiquitous images of RMB, U.S. dollar and Euro banknotes, or photos of construction sites. In short, rather boring!

Accordingly, to demonstrate that culture in business, especially in China, is an important intangible to factor in, we are now into our fourth series of featuring contemporary Chinese art on our magazine covers. For me, it seemed much more interesting, nodded towards the cultural aspect, and provided us with an unexpected bonus – several of the artists we have featured have now gone on to be highly collectible, and the firm itself has acquired many pieces that we originally featured as cover artwork. The practice, in featuring and purchasing these pieces, has now built up a fairly valuable private collection of contemporary Chinese art.

While practical knowledge and on-the-ground experience cannot be matched, a dash of cultural understanding also goes a long way in China, and it’s a point I have constantly strived to get across to investors – both the good and the bad aspects. Added value is all when providing a service, and Chinese culture, with its completely different linguistic platform, coupled with a mix of communism and Confucianism in its laws and social behaviors, certainly demands that extra know-how. With our China Briefing series of covers, I had a lot of fun in both choosing and obtaining some of the works that best illustrated, from a cultural viewpoint, the monthly business theme of the magazine. Here, I have chosen my ten personal favorites over the past few years, while the entire collection can be seen at our China Briefing Magazine archives.

I hope you’ll enjoy them as much as I have.

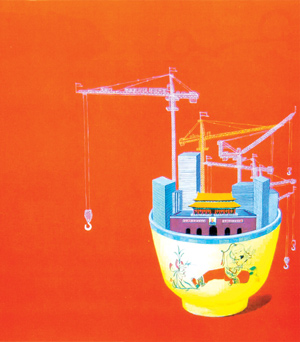

Zhang Tinqun “Constructing China”

Zhang Tinqun “Constructing China”

January 2007

This was the first of the contemporary art covers we ran, and I chose it as it really represented a lot about China at the time. The image of the modern constructions rising out of a traditional tea cup seemed to me a great blend of the old and the new that China had become. The colors were bright, optimistic and, for the artist, represented an “East meets West” theme as he uses Western oils rather than the more traditional Chinese implements. This particular piece also demonstrates the artist’s hope that ‘new’ China will not completely demolish the traditional. “Old” China can also be seen as a metaphor against uncalled for construction and re-development. Zhang Tinqun is a graduate of Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts; his pieces now sell for tens of thousands of dollars.

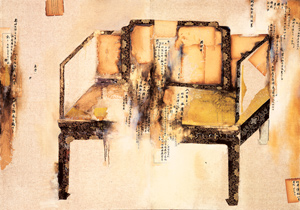

Wang Lifeng “Great Ming Dynasty”

Wang Lifeng “Great Ming Dynasty”

November 2007

Wang Lifeng is from Inner Mongolia, and a graduate of the Central Academy of Theatre in Beijing. Well known for his use of gold foil, silks and the use of Chinese seals, he focuses very much on the use of traditional materials to create his pieces. In this piece, the artist has focused on a Ming-style antique chair. Both broken and derelict, Wang nevertheless suggests a piece that may yet be restored to value and authenticity. Many contemporary artists demonstrate some unease with the pace of the development within China, Wang’s art is a good example of this.

Zhu Wei “Utopia No. 59”

Zhu Wei “Utopia No. 59”

December 2007

Zhu Wei graduated from the People’s Liberation Army Academy of Art and the Chinese Institute of Art in Beijing. Now highly collectable, he has had pieces displayed internationally, including Art Hamptons in New York, and has won many top awards. He is now considered the world’s most renowned contemporary Chinese ink painter and the art form’s most important explorer of technique. This piece, which we used to illustrate an issue about China’s Labor Law, merges both impressionist and communist styled themes. His works now run well into six figures in terms of US dollar value.

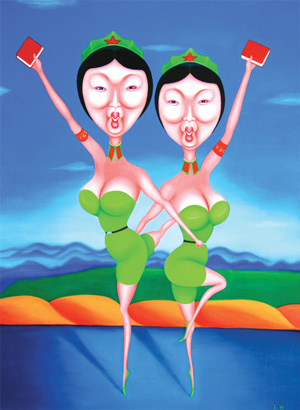

Zhao Yi “Red Lady Guard”

Zhao Yi “Red Lady Guard”

May 2008

Born in Shandong, Zhao Yi is a self taught artist who previously worked as a photographer. She set up her own studio in 2004 in Beijing. In her 2008 series of oil paintings, she turned to the Cultural Revolution era Chinese ballet “The Red Detachment Of Women” for inspiration and updated the Red Guards into bright voluptuous divas, dancing to a new revolution of China’s development with strength and determination. Her work is well known internationally and has become highly recognizable and collectible.

We used this piece for an issue devoted to managing joint venture partners in China.

Mandi Cao “Contract 1”

Mandi Cao “Contract 1”

January 2009

Mandi Cao was born in Tianjin, and attended art school in Australia. We used this piece for an issue devoted to individual income tax. Very bright scarlet, with traditional Chinese imagery and mixed media, the painting demonstrates the essence and tradition of Chinese culture. “I wanted to convey my emotions by using Chinese symbolic elements in my work,” Cao said of her Contract Series. “I chose to use hundred-year old contracts in my Contract Series because these contracts soon will disappear. I wanted to keep them in a way that still would carry their original purpose. They were meant to protect the stability of homes and companies and suggest the hope of prosperity.” She has also exhibited internationally and now has her own studio in Shanghai.

Xu Zhangwe “Landscape of the Great Era No. 79”

Xu Zhangwe “Landscape of the Great Era No. 79”

July/August 2009

Xu Zhangwe is the current director of the Huzhou Art and Design School. As an artist, Xu concentrates on building huge canvases focusing on the process of urbanization and modernization in Chinese cities such as Shanghai and Beijing. These massive pieces often depict city views from high above, as readers who have visited the top floors of Shanghai’s towering skyscrapers in Pudong will recognize.

Lu Wei “Guan Yunchang Gua Gu Liaoshang Tu”

Lu Wei “Guan Yunchang Gua Gu Liaoshang Tu”

December 2009

Lu Wei is from Shanghai and graduated at the Shanghai University Academy of Fine Arts. His oil paintings have been exhibited at China’s eighth and tenth national art exhibitions. He takes traditional Chinese themes and characters, and updates them in a more contemporary, almost cartoonish style. Again, the work demonstrates a potential trivialization of Chinese traditional standards in culture and social life.

Lui Jiutong “Huanghun”

Lui Jiutong “Huanghun”

January 2010

Liu Jiutong is a graduate of the Xi’an Academy of Fine Art, and is now based in Shanghai. He uses a combination of Western oils and Chinese inks, however uses a knife rather than a brush to create the look of many of his works. His pieces draw inspiration from the cities he visits, using the streets and buildings as subject matter for much of his current work. By unifying the thickness and slightness, bold and subtle, exquisite and simple, concrete and abstract, he is constantly exploring and trying new art style. He is a sought after artist especially in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore where his works are on almost permanent display at the top city galleries.

Chen Wenling “China Scene No. 2”

Chen Wenling “China Scene No. 2”

April 2010

Born in Fujian, Chen Wenling specializes in massive steel sculptures, and is a graduate of the Xiamen Academy of Art and Design, also completing studies at the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. His works have been displayed internationally. His pieces command high prices internationally through the auction houses, and can also be seen, often on beach locations to illustrate events or provide a startling backdrop to normal scenes.

Mao Xuhui “Golden Scissors”

Mao Xuhui “Golden Scissors”

June 2010

Mao Xuhui is originally from Chongqing, but graduated from the Yunnan Academy of Fine Arts in Kunming. Specializing like many Chinese contemporary artists in oils, his work has also been exhibited internationally and is highly collectible. Mao began to take “power” as a theme in 1989 with the Parents series of paintings. In 1992 he completed the Vocabulary of Power series. It was from the image of the “parent” that the “scissors” was developed. The “parent” is an iconic yet shapeless shadow seated on an overwhelming altar-like throne. It is aloof and awe-inspiring, like a religious icon. The stylized shape of the “parent” resembles a pair of scissors, and it gradually becomes one which, in the Scissors series, presides over domestic settings as the “parent” would sit upon the altar. The menacing presence of the scissors is compounded as an instrument of the everyday; as such it is a domestic as well as “democratic” symbol, carrying associated powers by being visually suggestive of the anthropomorphic god-like “parent” icon.

The entire collection can be seen at our China Briefing Magazine archives.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the principal and founding partner of Dezan Shira & Associates, establishing the firm’s China practice in 1992. The firm now has 10 offices in China. For advice over China strategy, trade, investment, legal and tax matters please contact the firm at info@dezshira.com. The firm’s brochure may be downloaded here. Chris also contributes to India Briefing , Vietnam Briefing , Asia Briefing and 2point6billion

- Previous Article Xinjiang and Tibet Raise Minimum Wages

- Next Article China Stocks Lose US$52 Billion in Q2