Stricter Chinese Food Quality Standards – Or Protectionism?

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

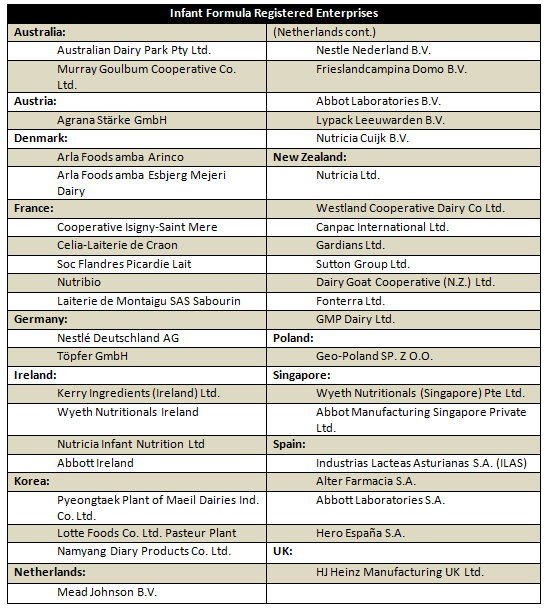

The apparently never-ending saga over foreign investment in China’s domestic dairy industry has taken yet another turn. In the aftermath of tainted Chinese milk products and to tighten quality control in the domestic market, China’s Certification and Accreditation Administration (CNCA) is now requiring all infant formula produced overseas to be registered with the nation’s quality watchdog before it can be sold in the country. Beginning May 1st, foreign infant milk suppliers were limited to an initial 41 foreign manufacturers from 13 counties, excluding some notable global brand names such as Abbott and Meiji.

Song Liang, a senior dairy industry analyst at the Distribution Productivity Promotion Centre of China Commerce in Beijing, was quoted in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post as saying “As far as we know, all the major imported infant formula brands sold in China have been approved.” Song noted that some big foreign brands, including U.S. and Japanese manufacturers, source their products in countries like Singapore, New Zealand or Australia. Only factories actually making the products need meet the registration requirements, he said.

As of May 1st, the list of approved foreign infant milk manufacturers is as follows:

Understandably, the list has upset a number of key global players and brands, many of whom feel they are being targeted to prevent them from accessing the Chinese market, while domestic firms are being allowed to fill in the supply gap. Song did acknowledge, however, that a secondary list of brands approved for sale in China will be released soon, on which notably absent foreign brands like Abbott, Wyeth and Friso are expected to be included.

China’s domestic dairy industry took a huge hit back in 2008 when plastics were found in infant formula manufactured by a Sino-New Zealand Joint Venture in Inner Mongolia, and has never really recovered. These were in the form of melamine, a toxic if ingested substance that falsely provides higher readings of protein than is actually in the product when tested. 300,000 infants were affected, with 54,000 hospitalised and six deaths. Much of the blame was levelled at corruption within the Chinese dairy industry itself, while Fonterra, the New Zealand partner, suffered a huge loss of reputation concerning its overview of the Chinese partner’s quality control and supply chain.

RELATED: Economic Cooperation to Play Stronger Role in China-France Relationship

The scandal changed the Chinese dairy industry overnight, with Chinese parents scrambling to get their hands on as much imported formula as possible. While Fonterra apparently tried to instigate a total recall, local Chinese officials prevaricated. Helen Clarke, then New Zealand Prime Minister, commented at the time: “I think the first inclination was to try and put a towel over it and deal with it without an official recall.” The incident went largely unreported in Chinese media – it coincided with the Beijing Olympics and no untoward publicity concerning Chinese domestic problems was welcome. Sanlu, the Chinese partner involved, eventually went bankrupt, while numerous Chinese nationals received prison sentences for their roles in corrupting the supply chain. Two were executed. Since that time, few Chinese parents have trusted domestically produced infant formula.

The issue was further compounded last year when Fonterra announced that they had found a botulism contaminant in 38 tonnes of protein used in the production of infant formula. The contaminant had been introduced into the protein in New Zealand. Affecting some 420 tonnes of infant formula already in China, the entire batch was recalled. The story made headlines, especially in China, where 80 percent of the domestic market is now supplied by foreign brands. This incident led directly to the new CNCA regulations. Questions remain over China’s handling of this case and regarding whether the new regulations were designed to prevent contaminants from getting into China-destined products or if this is just a handy tool to boost what has become a decimated Chinese domestic industry. The real answer is probably a bit of both.

But Chinese diligence on dairy products doesn’t just stop at infant formula – Chinese officials, under the guise of a fact-finding mission, recently asked to visit a British cheese manufacturer. One was selected and visited, whereupon the Chinese party proceeded to carry out a full production audit on what had been explained to British officials as a purely routine visit. As a result of that inspection (note: the factory does not even sell products to China), the CNCA has now banned all British cheese from being imported into China. It is believed that Chinese officials are now in discussions with the UK Foods Standards Agency to get to the bottom of the issue. The UK exports just 11 tonnes of cheese to China annually. Whether this is just an amusing, if awkward anecdote (one can imagine reactions to bacteria filled blue-veined cheeses), or part of China’s wider concerns over its sourcing of consumables destined for its domestic market, is hard to say.

Chinese officials have been conducting frequent audits of foreign manufacturers’ food processing plants over the past 18 months, and this is set to continue. If what they learn helps with technical upgrades of their domestic food processing industry, then this bodes well for international manufacturers of food safety devices. Much of China’s arable land is polluted and the nation faces challenges both in agriculture and in ensuring incidents such as the contaminated infant formula do not occur again. Regardless of whether foreign manufacturers regard these policies as discriminatory, the end result will likely be a step forward for food safety in China, and result in gains for foreign manufacturers with expertise in this field. Meanwhile, foreign investors considering selling dairy products for sale to China are now obliged to go through a whole new set of food safety evaluations. That is fair enough, although there are costs involved, yet still conveniently manages to ignore highly stringent food safety regulations in the West. The longer term implications of this could be construed as a desire to install a viewpoint that U.S., Japanese and EU products, despite their own food safety regulatory mechanisms, are somehow not to be fully trusted in China – a complete reverse to existing consumer sentiment.

Note: The newest issue of China Briefing Magazine, titled “Industry Specific Licences and Certifications in China,” contains a section dedicated to the food industry in China. Written by professional staff at Dezan Shira & Associates, it is now available for complimentary download for the rest of this month.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates – a specialist foreign direct investment practice providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to alliances in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, as well as liaison offices in Italy, Germany and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email china@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download our brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across Asia by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.

Related Reading

Industry Specific Licenses and Certifications in China

Industry Specific Licenses and Certifications in China

In this issue of China Briefing, we provide an overview of the licensing schemes for industrial products; food production, distribution and catering services; and advertising. We also introduce two important types of certification in China: the CCC and the China Energy Label (CEL). This issue will provide you with an understanding of the requirements for selling your products or services in China.

China Introduces New Consumer Protection Law

Economic Cooperation to Play Stronger Role in China-France Relationship

China Turns to Romania for Meat Supplies

- Previous Article Investing in China’s Future: The New Silk Road Economy

- Next Article China Debt Rises to 226 Percent of Annual GDP