Letters from America: U.S. Companies Selling to China – The Initial Evaluation Steps

A check list of things to consider and research when assessing whether to sell to China

This is Part XII of our ongoing Letters from America to Asia Series, featuring opinions and observations on America’s trade relations with China and emerging Asia from Chris Devonshire-Ellis.

Dec. 18 – In this column over the past few months we’ve provided a great deal of technical, statistical and demographic analysis accompanied by many tips for how American companies can best prepare themselves for selling to China. By this, I refer to American companies without a presence in the PRC who are now evaluating whether or not China may be a viable market for their product.

Within this series we have already explained how the increasing wealth of Chinese consumers – driven by State policy that has seen minimum wages throughout China increase by roughly 22 percent annually over the past five years – has begun and will continue to fuel a Chinese consumer boom. We covered this phenomenon and the opportunities this presents in China and Asia generally in the article “Selling U.S. Goods and Services to China.”

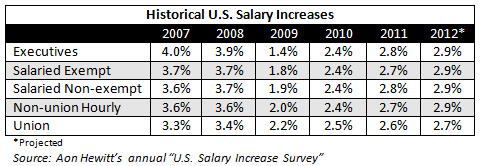

The extreme rate by which Chinese minimum salaries are rising can be fully appreciated by comparing that 22 percent average annual growth rate with the average annual salary increases in America, shown in the chart below:

China’s rapidly increasing consumer wealth – a government driven policy as it seeks to move away from an export-driven economy towards a more consumer-driven model represents, in what remains a closed economy with very little options other than to spend money domestically, a fast-growing middle class consumer base estimated to reach 600 million people by 2020. Clearly, the new consumer society that is being created in China is going to continue to develop – and in a nation where there are thousands of KFC, Starbucks and McDonald’s outlets in several hundred cities, the taste for American consumerism is already being introduced. These facts are being borne out by the most recent U.S. Department of Commerce figures that show America’s export sales to China are expected to top US$100 billion for the second successive year in 2012. The China market then is most definitely there. The question beyond that – and the answer to this specifically depends upon individual American businesses – is how can I access that market?

We covered the changing demographics in Chinese consumerism in the article “Growth in China’s Own Consumer Markets” in which I compared a number of obscure Chinese cities few people outside China have ever heard of, but with populations similar to Atlanta, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas, Memphis, Oklahoma, Seattle and San Francisco. In over 500 Chinese cities, consumers are upgrading from canvas slippers to Nikes, from green tea to lattes, and from cheap pants to Levis. Clearly, reaching out to China’s massive consumer base is now a possibility, and issues concerning distribution are now being solved with many expert players able to get your product to market. But in this article, we’re going to get companies started, and take a look at the initial questions that need to be asked. The first being – should I be selling to China at all?

There are many reasons why selling to China may not be such a good idea, and again these can vary tremendously. If your company holds proprietary patents crucial to your future success, your China risk of having that ripped off and used against you in a trade battle needs to be assessed. The Chinese can always manufacture more cheaply than you can in the States – so be careful about sending over technology that is critical to your survival. Patent lawyers may assist, but this remains essentially a business strategy issue. While it is wise to have your inventions and trademarks registered in China – even before you sell your product there – it is a key strategic decision for your company to assess what bringing your technology to China means – and how it could be used against you. Legal protection gives you some leverage, but a strategic evaluation of your IP is worth even more. Give that some thought before even calling the lawyers.

Another business aspect to assess is the type of product you have to sell. Many times during various trade fairs throughout the United States I have been given great local products. Examples include everything from Texan chili sauces to educational materials for schoolchildren – and I’ve been asked if they would be suitable for sale to China. There are many other cases, but just in these two there are issues to examine, as there are with all products under consideration to be sold in China. Firstly, to sell Texan chili sauce in China would require a fairly laborious procedure of getting the product as a consumable through the various Chinese health and safety regulations and licensing procedures, and this can be both costly and time consuming. Secondly, such a product – unless you can invest to getting it rebadged and repositioned as a desirable condiment for Chinese consumption – is likely to only appeal to a certain number of expatriates, and presumably mostly those from Texas. No doubt they’d be delighted to see Texan chili sauce bottles available in the expatriate-themed retail stores that exist in Beijing and Shanghai – but from what I can ascertain, expatriate Texans in China number in the hundreds, and not much more. It is true that certain industries (especially oil and gas) may have larger concentrations in major onshore oil drilling centers such as Shekou in South China or Bohai in the northeast, but other than that it would be hard to find a market. On that point: I checked, and there is no “Texans in China” Linked-in Group. Maybe someone should create one – because I have a client in Dallas that wants to sell you local chili sauce!

The lesson here is to ensure you have a viable product that can find a market. Common sense applies in most cases, but evaluating your product’s local capability to generate Chinese sales needs some discussion with people who have lived in China and are familiar with the market. Some decent advice from experienced hands about what is and what isn’t likely to work in the country can’t hurt either. Even when things begin to look rosy, a professional approach needs to be taken, and hiring a market research firm familiar with your industry will help assess what you have in terms of product and the costs of getting it ready for China.

As for the educational materials case – these are great products for schoolchildren, however there is a problem. China heavily regulates imported materials for use in classrooms and these need to be cleared by several ministries, including those for education, propaganda and culture. In addition, there are copyright design issues, the specter of plagiarism and possible U.S.-China cultural aspects to consider. “Ba Ba Black Sheep” isn’t a Chinese song, and many American cultural references in education, even to older students, may not be understood. An alternative strategic inroad here could be to sell to American and other international schools in the United States rather than China, and let them deal with the product cultural assessment, ministerial approvals and importation issues. Trying to do that in China from the United States would be a tough call. So in this case, it may well be better to find a facility with an operation in China, but sell them the product in the United States. That’s simple and easy, keeps China at arm’s length for you, and allows you to have a China market presence without taking any of the responsibility. So looking for American-based organizations that need your product in China still qualifies as a China strategy and it means you don’t have to get your hands dirty or invest as much.

Just these two examples demonstrate a strategic approach is required when it comes to assessing China as a potential market, and it is wise to talk about such issues with people that have China business acumen and can immediately relate to your product and its potential China fit. It happens to be something my firm discusses a lot with potential American clients, and a “no, it’s probably not going to fly” is far better advice than tears wasted down the road on frustrations and financial losses in trying to fit a square-shaped product into a differently-shaped consumer market.

Beyond these product evaluation issues, your own business and its America-China relationships need to be examined. Do you have internal infrastructure that can support export sales and staff familiar with the issues at hand? This includes everything from cross-border finance, shipping, and legal issues – within your own company departments. You will need to acquire staff that are familiar with import-export business, including the financial implications, and shipping. You will also need legal advice, especially when it comes to contracts. Hiring third-party American lawyers to draft contracts with China can become expensive. If you do, it is wise to use American lawyers who are registered with the Chinese Ministry of Justice and not just in their local state. Otherwise the U.S. firm will likely be subcontracting the work, and while there are some good China-savvy lawyers out there now back home in the States, and several Chinese lawyers now qualified in America, it is more ideal to use a U.S. firm registered and licensed to operate in China as well. We produced a list of foreign law firms – including American law firms – registered in China earlier in the year here. That was back in February 2012, so it will have changed, however it does provide clues as to who has been in the country for a period of time. If you need to acquire knowledge, and especially if you are expected to pay for it, it makes sense you spend that money on a real China guy and not a pretender. Checking the firm’s website for details of their China office is sensible due diligence strategy.

Continuing on the subject of acquiring professional China knowledge and contacts, the U.S. Commercial Service in China is very keen to help American companies export to China, it is a key part of their official trade remit. Building relationships with their trade officials both in the United States and in China is a very good idea and I personally have found them very friendly, knowledgeable and helpful. Incidentally, our firm, Dezan Shira & Associates co-wrote the U.S. Commercial Service’s “China Business Handbook” – now in its second edition and which may be downloaded for free at the U.S. Commercial Service China website linked to above (it’s the blue book on the homepage, and contains useful information about exporting to, trading with, and setting up in China). For companies with deeper pockets, organizations such as the U.S.-China Business Council provide a very corporate platform for interactions between American and Chinese interests, including B2G and G2G assistance. There is, again, a lot of useful research information available gratis on their website as well as more detailed reports available for purchase.

Beyond doing your China homework (and let’s not forget that China Briefing right here is both influential and has a subscription available here), many other American institutions can assist in helping you export your products to China. The Exim Bank provides attractive financing programs to support American exports overseas. We wrote about their facilities and the programs they offer in some detail in our article “Export Financing as a Key Component of U.S. Trade Strategy with China.”

In upcoming issues of the Letters from America Series, we will look at some of the technical, contractual, and IP issues American companies face when wanting to progress to actual sales agreements and getting paid. But for now, the above serves well as an introduction to many of the resources, institutions, and professionally-qualified research material that can be obtained when studying the initial question: Is China right for me, and how can I evaluate this?

In the meantime may I personally wish all our readers, friends and clients – both in the United States and elsewhere – a very happy festive season. It has been a blast working with many of you in the United States over the past few months. Letters from America will return in the New Year.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the founding partner of Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors in the China market and can provide due diligence services on Chinese companies in addition to advising American corporations on their China strategy. Founded in 1992, the practice has 12 offices in China and is a U.S. Department of Commerce preferred supplier. Please email the firm at china@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com.

Related Reading

An Introduction to Doing Business in China

An Introduction to Doing Business in China

Asia Briefing, in cooperation with its parent firm Dezan Shira & Associates, has just released this 40-page report introducing everything that a foreign investor should be familiar with when establishing and operating a business in China.

China Business Handbook

China Business Handbook

An excellent, complimentary beginners overview to conducting business in China may be obtained courtesy of the U.S. Commercial Service, whose “China Business Handbook” is now in its second edition and was co-written by our practice.

The Complete ‘Letters from America to Asia’ Series

A complete list of articles from our ongoing ‘Letters from America to Asia Series’ featuring opinions and observations on America’s trade relations with China and emerging Asia.

Chinese Outbound Foreign Direct Investment Faces Rigorous Scrutiny

China’s Provincial Outbound Direct Investment in 2011

Co-Investing in China with Chinese Partners

Delaware and Nevada Holding Companies for Chinese Foreign-Invested Enterprises

Double Taxation Agreements for China Investment

- Previous Article China Overtakes U.S. as the World’s Largest Filer of Patents

- Next Article China to Speed up Fiscal and Taxation Reform