A Guide to China’s Property Land Bank

Which cities have value, and which are overbuilt?

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Sept. 7 – One of the issues concerning China has always been the investment into property. For the past two decades, local and regional governments have used property investment to increase their GDP figures in order to meet Central Government targets. However, this has led to unhealthy reliance on property as a provider of growth, and many instances of corruption and collusion between officials and developers. China now has a massive property bank, spread across the nation, and the on balance sheet recorded assets of local governments have dictated that these have pushed prices in China up to astronomic levels.

Sept. 7 – One of the issues concerning China has always been the investment into property. For the past two decades, local and regional governments have used property investment to increase their GDP figures in order to meet Central Government targets. However, this has led to unhealthy reliance on property as a provider of growth, and many instances of corruption and collusion between officials and developers. China now has a massive property bank, spread across the nation, and the on balance sheet recorded assets of local governments have dictated that these have pushed prices in China up to astronomic levels.

Banks, meanwhile, have up until recently been lending large amounts of money to private Chinese citizens, often with very little collateral. Still-mortgaged properties have been used to borrow yet more money to fund additional purchases.

This has left the government with several dilemmas; rising prices are often pricing many young couples out of the market at a time when millions of square feet remain empty, the specter of a downturn in prices leaving many homeowners with negative equity, and those who have speculated facing potential bankruptcy. China simply cannot afford to rock the boat too much, yet a correction is deemed inevitable.

One of the problems now arising as a result of overbuilding to get assets onto balance sheets is the development of a massive property land bank across China. The question is, which cities have managed their property development well, and which have built regardless?

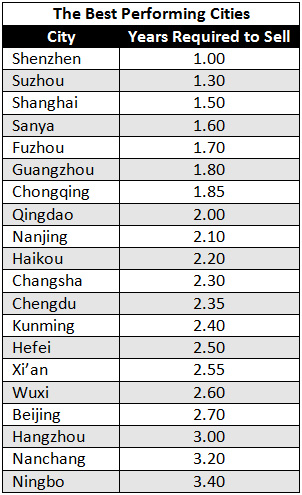

In these charts, compiled by Soufun, CEIC, and Credit Suisse, we can examine which cities’ land banks require what level of time to sell off. Such sales, will of course, have a bearing on potential value. The inventory level of each city is calculated based on land supply during the three year period 2008-10, and average demand (GFA) in each city for the same period.

These cities would appear to represent the best managed land banks, with healthy demand in many of them. That Shenzhen is at the top should be no surprise, the city has long had restrictions in place concerning migrant labor and this has both pushed demand up, and reduced the available area. Although the restrictions have now eased, it prevented the mass overbuild that occurred in many other cities. On the other hand, Sanya is booming and again has limited build. But there have been issues with only 30 year leases being granted, suggesting property there may not be a sound long-term investment to pass down the generations. The conclusion therefore can only be that while the above appear well managed, it pays to understand the local factors that can affect the likely future value. China’s property investment is still a very localized issue and what works in one city may not in another.

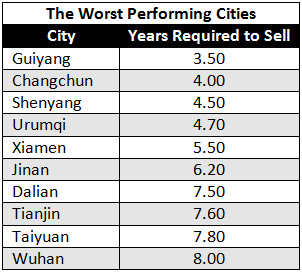

Simply put, one can at a glance note the cities that have way overbuilt, and they include some surprising names: Tianjin, Dalian and Xiamen among them. The reasons for this are many and varied, but may be indicative of government setting too high a premium on land close to development zones, and expecting large numbers of property investors to pour in to live in close proximity to their factory investments. That clearly has not happened.

Take Tianjin for example. While it possesses a massive port and free trade zones, and is only 30 minutes away from Beijing, at present a population other than the long term local market is not moving in. That can be seen in some manner by the numbers of expatriates in Tianjin. Tianjin’s population is 9.5 million, Beijing’s is about 12 million. Yet Tianjin is notable for a lack of expatriates in any numbers. While manufacturing FDI remains high, that has not translated into commercial property. Foreign investors – including those from other parts of China – simply do not want to live in Tianjin. The lure of the high-speed rail it seems, has not yet proven strong enough to justify the build or the cost.

Much of Dalian has been built up along the coast, and although it is an attractive city, a combination of overbuild and inflated prices had left a huge number of properties empty. Wuhan, on the other hand, just seems to have completely left the planet. Clearly, an eight-year timeframe to offload the property built is symptomatic of some very poor planning and almost certainly some write-offs will need to be made. What are assets today may, quite literally, become derelict.

Economists I have spoken to about the matter have stressed that it is not a problem. Many have suggested that the empty apartments will be taken up by migrant labor as more people move into cities. I don’t believe that is credible for as long as the current price levels are maintained, despite minimum wage levels being doubled by 2015.

Another example not listed here is Manzhouli, where the local government has built a city capable of holding 5 million people and an airport to match. Yet the actual population of Manzhouli is just 250,000. To reach passenger capacity at their airport, the entire population of Manzhouli would need to use the facility once every three weeks.

The pricing problem is caused by local governments being set GDP growth figures during the past 20 years. In using property development to do so, they have tied property asset prices at levels to match the Central Government’s expected GDP targets, not on real value. The result has been an explosion of over-valued property, and far too much of it.

The government is not in a position as yet to do much about it, yet clearly in many cities the building has to cease. In others, such as in Shenzhen and Shanghai, there is demand. A correction at some point however must be due, purely in order to shift empty units. It’s clear that China’s property problem is not a national one, which is good in part as a decline on a national basis seems unlikely and is not required. But for the cities that have overbuilt, I’d expect to see housing schemes funded in part by the Central Government to get lower paid workers into those properties. The local governments concerned may also have to take haircuts on some of those inflated assets. In which case, the local government investment trusts in the cities concerned should be looked at very carefully for signs of potential default.

In the meantime, as Dong Tao, Managing Director of Credit Suisse China pointed out yesterday, “China property is too expensive. Investors should look at the United States, and Europe for some bargains. Take Greece for example. In a couple of years you’ll be able to buy an entire island for the amount it costs to buy a duplex in Wuhan.”

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the principal and founding partner of Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm provides legal, tax and business advisory services to foreign investors in China, has a 20-year history and maintains 12 offices throughout the country. Please email the firm at info@dezshira.com, visit the practice at www.dezshira.com or download the firm’s brochure here.

- Previous Article Africa Welcomes China’s RMB Internationalization

- Next Article China Law Deskbook Legal Update – Sept. 2011