The Rough Guide to the Cost of Business in China – Compared to Asia

High tax rates and ever-increasing wages are making China non-competitive

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Oct. 4 – China will hold the Third Plenum of the CCP in November, and this is a traditional forum for the country to roll out reforms and introduce new policies. One of the major issues facing the government is how to re-balance the economy. Concerns are being leveled at all stages across Asia and beyond as to whether the government of Xi Jinping can successfully transition the country to a consumer driven economy, while at the same time holding onto what is a significant global manufacturing base and continuing to make the nation attractive to foreign investors.

The latter two issues are coming under increasing attention and are vital for China to deal with as the country struggles with lower growth rates and increasing operational costs. The old development model – essentially spearheaded by Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji over 20 years ago, saw China emerge as a low cost destination for global manufacturers. Local labor was cheap, tax breaks of up to five years attracted foreign investors, and the corporate income tax rate for those same investors could be as low as 12 percent in some areas of China and a regular 15 percent for others.

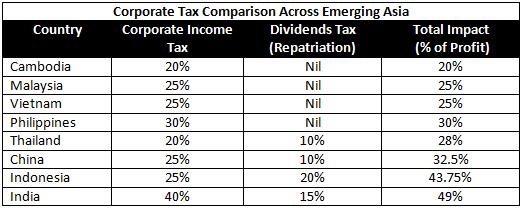

These tax breaks and low rates for investors were scrapped by the government of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao in 2008, and have now risen to a corporate income tax rate of 25 percent plus another 10 percent on top of that for foreign investors to repatriate their profits. Although it is true to say that a number of China’s double tax treaties reduce the dividends tax from that 10 percent burden to 5 percent under certain circumstances, it still represents an effective doubling of the corporate tax burden from 15 percent to 30 percent in the past five years. That has coincided at the time when recession has hit many North American and European Union countries hard. Both are among China’s largest trading partners, and absorbing such a hike for MNC investors into China has proven troublesome.

In addition to the income tax increase in China, alternative destinations have started to emerge as competitors. Here is a rough guide to how China stacks up in terms of its corporate income tax burden against its Asian competitors.

Please note: the amounts mentioned under salaries, welfare, VAT and CGT are “rule of thumb” and should be used as guidelines only. This is due to the various complexities of calculating and assessing amounts across countries, while attempting to standardize differing cross border measurements and tax treatments for general comparison purposes). For complete details and comparisons, please email asia@dezshira.com.

As mentioned, the dividends tax burden can be reduced by half under certain treaties. It is also worth noting that India, currently tax expensive as a destination, is expected to pass a bill within the next 18 months that will reduce its corporate income tax rate to 30 percent and its dividends tax to 10 percent. That won’t make China the least tax attractive destination, but it does continue to make it far less attractive than the other Asian Tigers such as Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines.

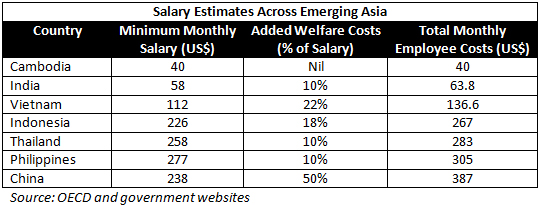

Of additional concern has been the relentless rise of wages in China. While the government quite rightly wants to improve the financial well-being of the average Chinese national, the stark fact remains that for China, internal political pressures on the government to keep the prosperity of Chinese nationals on the up is happening at a far faster rate than that of anywhere else in Asia. Quoted above are the mean average minimum salaries, which means that for China and India especially, a large degree of movement can be found either way of the figures quoted, and especially at the higher end (the average monthly salary in Shanghai now is over four times the US$238 quoted above at US$1,133 and in Mumbai now about US$550). But where China’s employment costs really start to get above what should be a regional mean is in the extraordinary cost of mandatory social welfare – 50 percent of salary. This is a somewhat unique situation and again demonstrates the cost of doing business in what remains a one-party state determined to maintain social order by giving its work force increasing amounts of money. That may be absorbable by the country’s numerous state-owned enterprises, but it is becoming an unattractive proposition for foreign investors.

Finally, a note on the other figures quoted: many of the countries mentioned do not actually impose mandatory welfare – the figures have been based instead on what is considered normal corporate practice. But in China, that 50 percent addition to the cost of salary is a legal requirement to be borne largely by the employer.

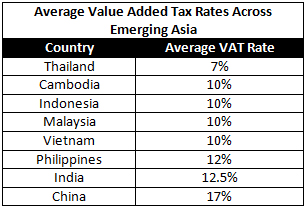

Another area where China scores big in expenses is in value added tax, most of which is claimed by the treasury. Additionally, VAT is not fully claimable on export, meaning an additional cost of business exists there also. China imposes the highest VAT rate in emerging Asia, impacting on every single product, again adding to the cost of doing business and living in the country.

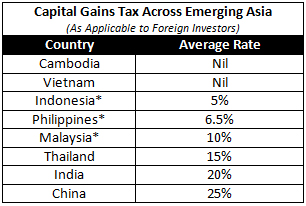

*Capital gains tax applications vary, and Indonesia, Philippines and Malaysia above only charge CGT on property transactions. China and India charge on all gains, although China’s CGT rate remains the highest in emerging Asia.

Summary

It is to be hoped that the Third Plenum in November will introduce some tax reforms into China to alleviate what is fast becoming a very expensive Asian destination to invest in. The increase in the amounts of China’s fiscal tax collection and the overall cost to foreign investors in China in particular has arisen rather at a rather unfortunate time, after all it is hardly China’s fault that the West has been in recession and growth in the United States and EU remains patchy. Nonetheless some strategic and long lasting decisions need to be taken.

Cost of labor

It will be difficult for the government to address this; Chinese nationals have become used to ever-increasing standards of wealth and disposable income. Yet this has risen, and the national expectations along with them, at far higher rates than is actually sustainable. At the same time, living conditions and the ability to tap into welfare have decreased. Getting more money into the hands of the pockets of the Chinese is not a sustainable solution; getting the national welfare system onto an insurance based model is. China’s main concern is its aging population, and how to look after them. That has been confused with wage increases. The sooner China can introduce foreign financial institutions to assist with spreading the burden of China’s elderly through an insurance backed scheme, the slower the pace of China’s increasingly expensive workforce needs to be, and a more competitive labor force in line with the rest of emerging Asia will result. If you can swap part of the mandatory welfare burden – which falls purely on employers – onto an insurance based welfare scheme partially backed by international institutions then more money can go into overall corporate profitability for future investment.

Income tax

The rate is currently too high. Plus the “dividends” tax – which falls purely on foreign investors – adds an additional burden in profitability costs over and above what Chinese companies have to pay. That is not a level playing field, and investors are moving elsewhere as a result. Scrap the dividends tax and reduce CIT to 20 percent from 25 percent.

Value added tax

Although this is a consumption tax, and largely borne by the Chinese consumer, it is still the highest in emerging Asia. Surely when trying to stimulate a domestic economy to buy more, a reduction in VAT would help. A reduction in VAT to 12.5 percent from the 17 percent should be effective immediately with the rate only climbing back up again in 1 percent annual increments in line with a rise of Chinese overall domestic consumption.

At present, China’s tax regime and cost of business platform are too high, and are running far out of synchronization with emerging Asia. Rather than the Chinese leaders thinking the country is comparable to Japan (apart from the economic size, it is not), China needs to realize it is still very much an emerging economy and should begin to tailor its reforms accordingly. Chinese nationals in Nanning earn three times those in Hanoi, pay double the costs, and have no better overall living or disposable income standards than their Vietnamese counterparts. The cost differential doesn’t make sense. As for foreign investors, the bean counters will be sharpening their pencils. The rule of thumb appears to be that if you can get manufacturing productivity up to 70 percent of that currently achievable in China, then it usually makes financial sense to relocate. And with ASEAN’s free trade agreements with China kicking in fully come 2015, the Party need to introduce some serious reforms and policies in November to head off what has the potential to turn into a slow decline in China’s overall fortunes.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates, a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. For more information, email asia@dezshira.com or visit the practice at www.dezshira.com.

Related Reading

Expanding Your China Business to India and Vietnam

Expanding Your China Business to India and Vietnam

This issue of Asia Briefing Magazine discusses why China is no longer the only solution for export driven businesses, and how the evolution of trade in Asia is determining that locations such as Vietnam and India represent competitive alternatives. With that in mind, we examine the common purposes as well as the pros and cons of the various market entry vehicles available for foreign investors interested in Vietnam and India.

Are You Ready for ASEAN 2015?

Are You Ready for ASEAN 2015?

ASEAN integration in 2015, and the free trade agreements China has signed with ASEAN and its members states, will change the nature of China and Asia focused manufacturing and exports. In this important issue of Asia Briefing we discuss these developments and how they will impact upon China and the global supply chain.

Establishing a Business in India

Establishing a Business in India

In this issue of India Briefing Magazine, we discuss establishment structures in India, including liaison offices, project offices, branch offices, and wholly owned subsidiaries. We overview each structure in terms of the situations in which it is appropriate, its permissible activities and limitations, as well as its setup and winding up processes, complete with flow charts.

100% FOEs, JVs and the Promotion of Supporting Industries

100% FOEs, JVs and the Promotion of Supporting Industries

In this issue of Vietnam Briefing Magazine, we examine the different types of legal entity that can be established in the country. This issue offers a clear snapshot of up-to-date regulations and specific changes to foreign investment policies, as well as a useful summary of tax incentives and exemptions. Also, a road map and timeline for licensing procedures take the guesswork out of this initial step in establishing a business in Vietnam.

Selling to China & India’s Middle Class – It’s a Vietnam Manufacturing Play

China & Malaysia to Increase Trade By 60%

Moody’s Upgrades Philippines Rating

Xi Again Proposes an ASEAN Infrastructure Bank

- Previous Article China Release Draft Plan to Develop its Online Retail Industry

- Next Article Chris Devonshire-Ellis at APEC – Exclusively on Asia Briefing