Changing Bhutan Eyes China with Caution

This is the twelfth in a series of articles that looks at China’s borders. As China has grown in the last 30 years, so have the often complicated relationships it has with its many varied neighbors. In this article, we take a look at Bhutan.

By Joyce Roque

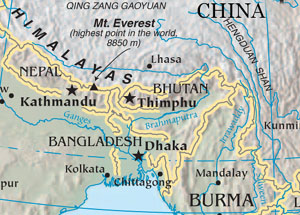

Sept. 8 – Bhutan shines like a jewel wedged between China and India. It remains one of the most mysterious places on earth -the land of stunning mountain ranges where mystics and monks have long searched for spiritual enlightenment.

The country’s name comes from the Bhutanese term, Druk Yul, or “Land of the Thunder Dragon.” Bhutan is the only Vajrayana Buddhist nation in the world. Its policy of cultural isolation has served well to preserve much of its traditions and religious teachings leading some people to refer to it as the last Shangri-la.

It only opened up to outsiders in the 1970s and today tourism remains tightly regulated. In 2007, only 21,000 tourists traveling in groups were allowed to visit while individual travel is still discouraged.

The country is small, spanning an area of 38,364 square kilometers with a population of 658,000. Bhutan relies heavily on agriculture, tourism and hydroelectric power for income.

It is a poor and isolated place.The same grand mountains that make the country beautiful is also part of the reason why building roads and infrastructure can be difficult and expensive. A glimpse of Bhutan in the 1960s would have shown a country with no telecommunications systems and no roads. Television and internet would only arrive in 1999.

The country has been ruled by the monarchy led by the Wangchuck family since 1907. In 2005, then reigning King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, begun the campaign to draft the first constitution for democratic reforms that would peacefully transfer the country from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one.

The following year, he abdicated the throne to his eldest son, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The move allowed the Oxford-educated monarch to assume the throne until general elections were held in 2008.

The following year, he abdicated the throne to his eldest son, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The move allowed the Oxford-educated monarch to assume the throne until general elections were held in 2008.

On March 2008, Bhutan’s first parliamentary elections were successfully with Jigme Thinley becoming the country’s first elected prime minister and leader of the pro-monarchy Bhutan Harmony Party that would win 44 out of the 47 parliamentary seats.

The happiness quotient

Despite the poverty, what remains striking is how the country seems happy. There are no beggars or homeless people on the street. No one is hungry. The average wage of a Bhutanese may be low but the land is fertile and its population small; one only has to turn to the land for food.

The Bhutanese government spends an estimated 18 percent of its budget on providing free education and medical care to all Bhutanese. In Adrian G. White’s study, “A Global Projection of Subjective Well-being,” the country was at 8th place out of 178 countries under the category despite having a low GDP.

Instead of following economic standards, Bhutan opted to listen to its own heart and address the subject of happiness instead. In 1972, then reigning King Jigme Singye Wangchuck introduced the program, gross national happiness (GNH) that would be guided by Buddhist spiritual values to enforce policies that would improve the quality of life in holistic and psychological terms.

In it the King would be quoted as saying, “gross national happiness is more important than gross national product” because “happiness takes precedence over economic prosperity in our national development process.”

The concept of GNH works on the premise that the development of human society happens when both material and spiritual development complement each other. Its four guiding principles are: promotion of equitable and sustainable socio-economic development, preservation and promotion of cultural values, conservation of the natural environment, and establishment of good governance.

Despite Bhutan’s utopian ideals, the country has not been without violence. In the late 1980s, Tibetan-based Bhutanese culture measures led to violent ethnic unrest from the country’s Nepalese community which led to an estimated 80,000 Nepalese fleeing to nearby Nepal.

Border issues

It is striking how Bhutan compared to China’s other border countries has all but turned its back on it. Currently, Bhutan has no formal diplomatic and trade relations with China. Its only solid link with the latter is its close cultural and religious ties with Tibet. In addition, it has no resources like gas reserves and minerals that would normally attract heavy investment from its giant neighbor.

For much of its modern history, Bhutan has always been under the sway of India. The country is its top export and import partner. India also provides more than half of Bhutan’s development assistance amounting to US$616 million. By 2020, India promised to import a minimum of 5,000 megawatts of electricity from Bhutan. India will also be funding three hydropower projects in the country worth a total of US$1.2 billion with a combined installed capacity of 1,400 megawatts.

Indians and Bhutanese are free to cross the border visa-free and the Indian rupee can be used in Bhutan as well. Major businesses in the capital are run by Indian merchants. Even the Indian car company, the Tata Group, has built a five-star hotel in the capital.

On the occasion that Bhutan does engage China it is always in regards to its borders. China’s interest in Bhutan is clearly strategic. The country shares a 470 kilometer border with China but has four disputed areas that stretch from Doklam towards the ridges from Gamochen to Batangla, Sinchela, and down to the Amo Chhu- all in all 269 square kilometers.

When the Chinese Communist army seized Tibet in 1950, Bhutan was afraid that its sovereignty would be compromised because of Chinese claims to Bhutan as part of a greater Tibet. This led to the closure of the Tibetan-Bhutanese border in the north.

Tense border disputes would put Bhutan on the defensive on what it sees as continuing Chinese advances in its territory. It would only change its tact in the ‘70s when it supported the “One China” policy and voted for China’s seat in the U.N. In 1974, Bhutan invited the Chinese ambassador to India to attend the coronation of King Jigme Singye Wangchuk.

Finally in 1998, China and Bhutan signed an agreement promising peace on the border and China recognizing Bhutan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity called the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence. But by 2002, China would try again and passed claims of ownership over the disputed areas. Three years later, Chinese soldiers would be found crossing the border into Bhutan.

China’s latest foray into Bhutan was in 2007 when the People’s Liberation Army started making inroads near the strategic Chumbi Valley, a stretch of land that lies in junction between India, Bhutan and China. The move alarmed Bhutan and India due to the valley’s proximity to the often volatile Siliguri Corridor.

The region will likely see increased activity by both Chinese and Indian forces in the future as the countries move to secure their strategic interest. Bhutan, like Laos in Southeast Asia, will see its future irrevocably shaped by its powerful neighbors.

This is the twelfth in a continuing series that focuses on China’s borders. The complete series to date can be found here.

For more commentary on the emerging nations of Asia, please visit out sister website, www.2point6billion.com. For Bhutan-specific news, please see:

Bhutan Becomes a Democracy

Dissolving Investment Barriers

Why India and China Love to Disagree

Uniting for a Cleaner Future

- Previous Article Draft Law to Allow Exchangeable Bonds

- Next Article China to Continue International Investment Cooperation